Introduction

Hyelaphus porcinus (Zimmermann, 1780) commonly known as Hog Deer or Paddy-field Deer is a medium-sized ungulate which belongs to the family Cervidae. Keelart in 1852 described the Hog Deer as a taxon unique to Sri Lanka and called it Axis oryzus. Pocock (1943) synoymised this taxon as a subspecies under Axis porcinus Zimmermann, 1780. This is further justified by recent research carried out on the species by the authors and co-worker that this species is indeed a unique species to Sri Lanka (C.S.R. Nanayakkara pers. comm. 2011). It was thought that the Hog Deer was introduced to Sri Lanka. However, it has not been documented in literature, while every product of commerce and alien species brought into Sri Lanka was documented (C.S.R. Nanayakkara pers. comm. 2011). Literature and records dating back to almost 400 years were referred and although many species of flora and fauna were taken out none was brought in at the time. None of it indicates that the Hog Deer was introduced to Sri Lanka. Incidentally there is a record of the Hog Deer being exported to Australia from Sri Lanka Yapa & Ratnavira (2013). It is counted as one among the smallest deer species in the world and also regarded as one of the most primitive species of deer. As a species the Hog Deer has some peculiar characteristics, the body being long and the legs relatively short. The adult Hog Deer reaches a shoulder height of approximately 60cm with a dark brown pelage, often with white tips giving a speckled appearance. Whereas the juveniles bear white spots which they lose as they mature, males possess backward pointing antlers that reach approximately 30–35 cm in length. The “Hog Deer” is named so, because of its unique way of running; the head is hung low, like that of a hog while the animal runs, which helps the animal in ducking obstacles in its way rather than leaping over them (Anonymous 2005).

It has a wide distribution in the Asian region from Pakistan to India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka where it inhabits grasslands, riverine forests and coastal areas and a well-documented introduced population is found in Victoria, Australia (Phillips 1935). The Hog Deer is a rare and shy animal which is nocturnal in habit and is only found in the wet zone of the island. It inhabits a narrow stretch of the coastal belt in the southwestern part of the island from Kalutara to Galle, stretching inland for 20–30 km (Phillips 1935). It was particularly common in the marshes round the Ambalangoda, Telwatte and Matugama area and along the Bentota River. However, after the 1930s there is a dearth of records on the Hog Deer. Due to habitat destruction and hunting taking its toll on this species it was considered that the species had become extinct in the wild by some researchers in the early 1970s. However, there were sporadic records of this species from cinnamon plantations in the Galle District and the subsequent study in 1992 by McCarthy & Dissanayake (1994) gave a consensus to the exact status and distribution of this cervid. It was found to inhabit a 35km2 triangular region in between Elpitiya, Induruwa and Ambalangoda (Fig. 1).

According to the IUCN Red list of 2007 which was compiled by the IUCN Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, the Hog Deer in Sri Lanka is an endangered species due to the decline in extent of occurrence, area of occupancy, area extent and or habitat quality and decline in population size. Yet, there is a dearth of information on the ecology and the area of occupancy, which remained unclear for several years. The present study was carried out for a period of one year from March 2009 to March 2010 to assess the current distribution and status of the nominated species to support their in situ conservation management.

Materials and Methods

Since this species is nocturnal, elusive and occurs in low numbers, it was extremely difficult to carry out a census. This specific problem was minimized by the use of a variety of techniques such as dung pile counting, measuring of hoof prints and any signs of feeding to do a census on its abundance rather than measure the density. Since the Hog Deer is a threatened species (IUCN 2007), certain precautions have to be taken when developing a methodology to study this species since capturing, tranquilizing or caging is not allowed under the fauna and flora protection ordinance. Hence, information was gathered only by means of direct visual observations, dependable indirect signs such as deer tracks and hairs. Following the standard methods given in Sutherland (1996) and through an open ended questionnaire survey (Keneth 2005) given to local people wherever possible.

Study area

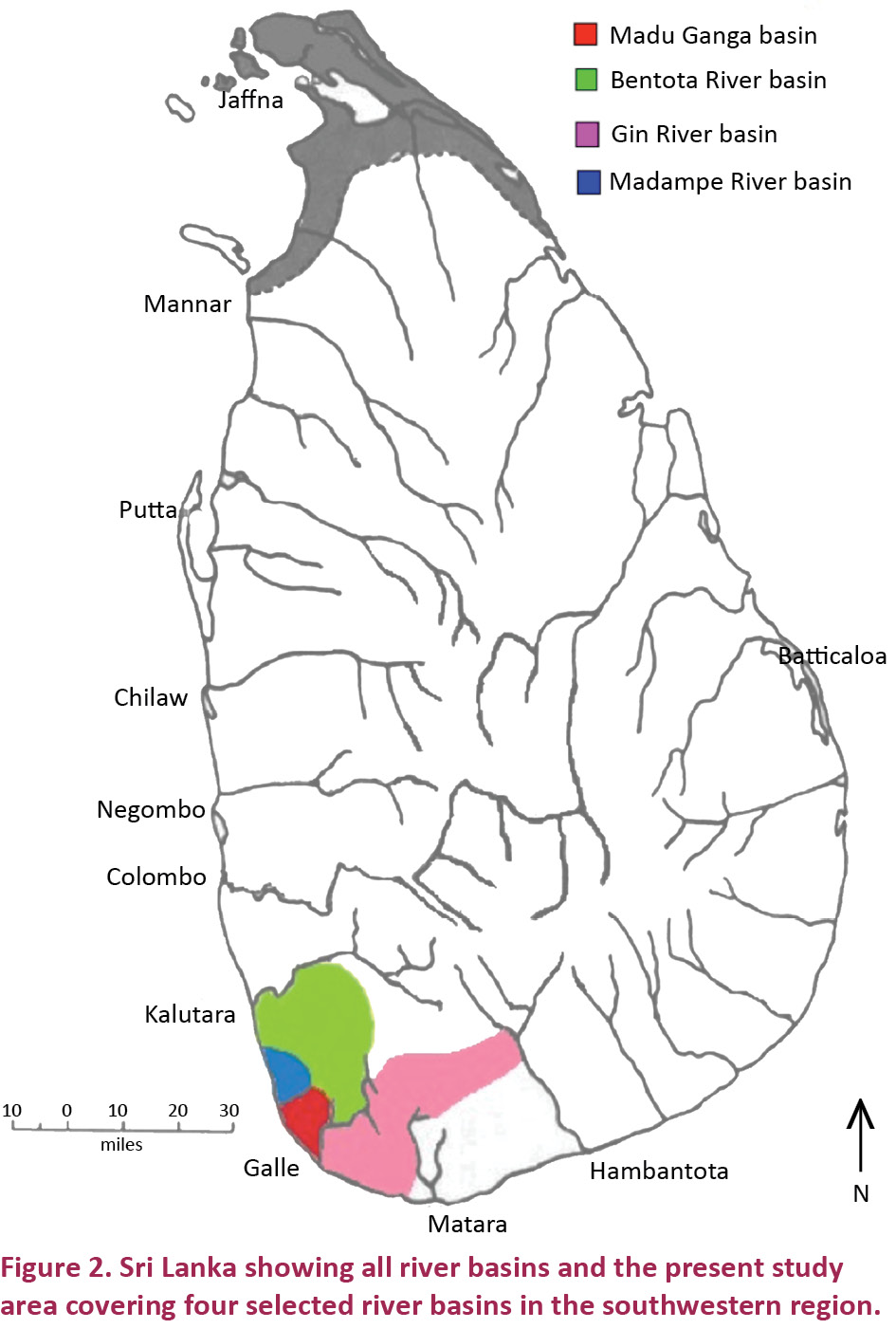

The present study was conducted in two administrative districts, which are densely populated, i.e., Galle and Kaluthara in the southwestern region of the Island where a few fragmented rain forest reserves, i.e., Kanneliya, Kottawa, Hiyare, Hiniduma, Yagirala and Beraliya-mukalana as well as several agro-forest lands of cinnamon, tea, rubber, coconut, oil palm and paddy are found (Fig. 2). The area also harbours other types of habitats like shrub lands, marshes, mangroves and riverine areas belonging to four perennial rivers; Bentota, Gin, Mãdu and Madampe. Hence the study covered an area of approximately 750km2.

Field survey

During the course of the field survey a 5x5 km grid map was employed to cover the entire study area putting all possible efforts to cover at least a single side of the plots by walking, hiking or on a non-mechanized boat especially in riverine, mangrove and marshy areas. Since the study area is large these virtual plots were used to cover the study area and an area as much as possible was covered in each plot. Firstly a selected area within a plot was disturbed in an innocuous way to make the animals flee; while six to eight people were placed at vantage points to survey the area that was being disturbed to monitor fleeing species of mammals. Harmful methods such as fire crackers, firearms or any noisy equipment which would lead the animals to permanently leave their roosting sites were not used. Later the same plot was carefully observed for any prospective evidence, e.g., Deer-tracks, crop damage and pellet groups to prove the occurrence of the species.

Once the presence of the nominated species was confirmed either through direct or indirect observations the date, number of individuals seen, habitat type and other special observations were noted down. The GPS location was also noted using a Garmin 12 hand GPS receiver and mapping was done later using ARC GIS version 9.3.1.

Hog Deer track identification, differentiation and evaluation

Given the Hog Deer’s shy and nocturnal habits it is difficult to carry out studies on its distribution based only on visual observations. Hence the use of other accepted indirect methods of study were also considered. Deer tracks that play an important role in determining a variety of features about an individual or number of deer such as sex, the direction the deer was travelling, size and age of the animal (Anonymous 2007). There was no controversy as it was quite easy to work since there was no other species of deer similar in size to the Hog Deer in the survey areas, except for a few records of Barking Deer Muntiacus muntjak from Kanneliya, Kottawa and Hiniduma forest reserves where Hog Deer were totally absent. On the other hand the hoof print of Hog Deer can be set apart from other hoof prints of ungulates due to its medium size as well as the gap between the two hoofs. It is highly adapted for walking or running on muddy terrain, whilst running the hoofs become erected. The more commonly seen tracks were that of Wild Boar Sus scrofa, whose tracks can be differentiated from Hog Deer tracks by its blunt end and much rounded shape. During the course of the study a small herd of Spotted Deer Axis axis ceylonensis was recorded in the designated area of study. This herd had once been kept in a plantation as domestic animals, but later on due to certain restriction the herd had been released to the wild. Because the hoof print of the Spotted Deer is much larger than that of the Hog Deer and the hoof print of Spotted Deer fawns can be set apart from the Hog Deer, as the gap in each hoof is wider in the Hog Deer, as such it did not by anyway hinder the research.

Pellet groups evaluation

Evaluation of pellet/dung piles is another well accepted method for identifying different species of deer (Anonymous 2008), but it could be a bit confusing if domestic grazing animals such as goats are present, as their dung piles are similar to that of Hog Deer. Since the goats were present only near human settlements there was only a slight chance of confusion. The size of the pellets and number of pellets depends on the age and size of the animal. Smaller individuals drop small pellets and it consists of about 45–60 pellets in one cluster. Compared to the size of the animal, Hog Deer have much larger pellets than that of the Barking Deer, but much smaller than that of the Sambar Rusa unicolor and Spotted Deer Axis axis ceylonensis.

Crop damage evaluation

If crops such as paddy, cinnamon, yams and vegetables are frequently damaged at night, it is a good sign that there is a species of deer in the vicinity. Hog Deer prefer to feed on the tender shoots of paddy and saplings and shoots of cinnamon and also various types of vegetables. This damage is evident even after several months in cinnamon plants as the plants become bushy due to the apical shoot being damaged.

Information gathering from local people

Randomly selected villagers from the survey area were interviewed using an open ended questionnaire and a photographic guide of the species of deer found in Sri Lanka was used for the identification of the species. The interviewees were from different walks of life such as Buddhist monks, farmers, land owners, plantation workers (cinnamon and tea), fishermen, hunters (poachers), caretaker (plantation), boatmen and sand miners. Thus, a total of 356 people in 52 villages spanning the entire area of study were interviewed.

Conducting awareness programs

Awareness programs were conducted using posters as well as delivering lectures whenever possible for school children, farmers and social workers in identified areas especially in areas where relic populations of Hog Deer were found.

Results

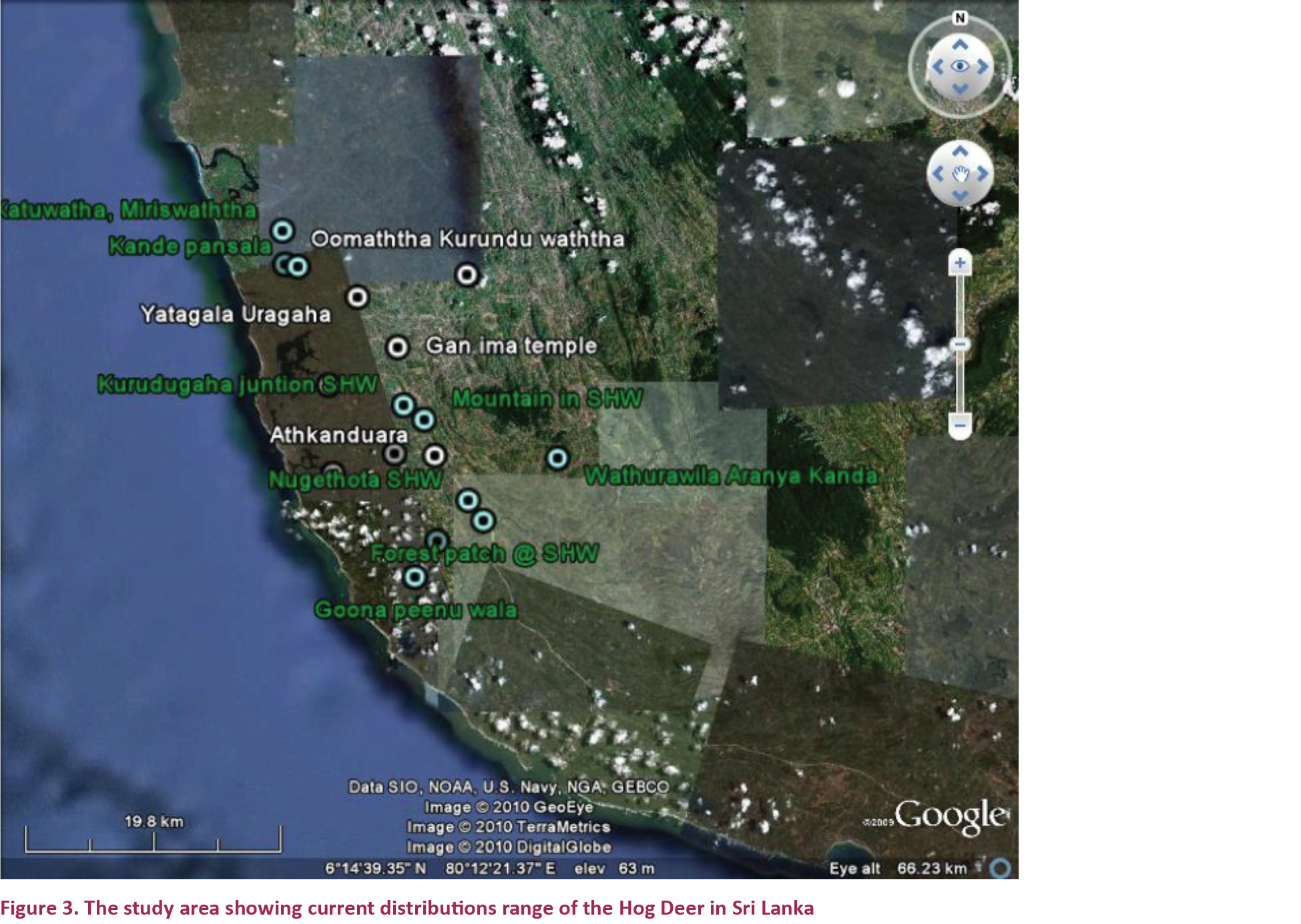

The present study granted a similar value to direct sightings and indirect signs, and could enumerate a total of 23 confirmed Hog Deer occurrence sites in an area that lies within two major river basins namely Bentota and Gin, covering an area of approximately 220km2 in the wet zone of the island. Figure 3 is the map of the area surveyed showing the current distribution range of the Hog Deer in Sri Lanka. Its northern most point (6023’187”N & 80008’570”E) is a village called Katuwatta in Miriswatta an area 5km inland from the coastal belt whereas the southernmost point (6009’150”N & 80008’570”E) is 3km south of Gonapinuwala Town. The eastern most points were Wathurawila Arannya Kanda, a rain forest patch about 18km inland from the coastal belt and a cinnamon plantation named Omatta kurudu watta 16km inland from the coastal belt. The western border lies about 3–7 km inland and parallel to the coastal belt.

During the questionnaire survey with local inhabitants, two records of the Hog Deer occurring outside the Benthara River basin from Udugama and Yagirala remained unconfirmed, and further evidence is needed to confirm the occurrence in these areas, as it does not compute with the documented distribution of the species. Through the interview survey with local inhabitants, 23 locations out of 53 were identified as possible sites of Hog Deer occurrence, out of which seven were confirmed by the authors, as to the presence of Hog Deer through field observations such as deer tracks (Images 1–3), crop damage (Images 4–5) and dung piles (Images 6–8). In addition two sets of antlers and nine captive animals (two bucks, three females and four fawns) were also recorded from the area surveyed (Image 9).

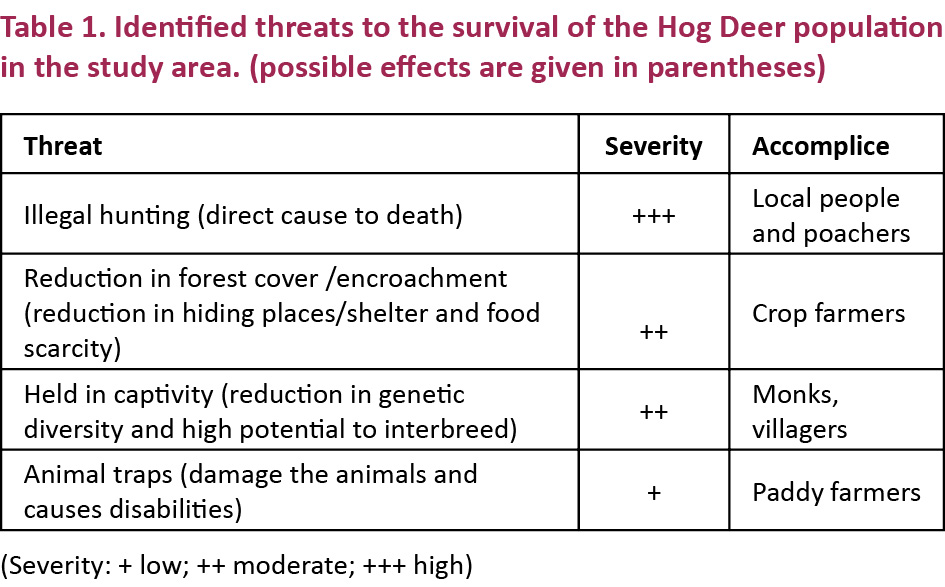

There are a number of threats, which affect the existing population of Hog Deer in the survey area which are given in Table 1. Among them illegal hunting was the most severe threats compared to others. However, a total of 132 local people out of 356 interviewed confirmed the existence of relic populations of Hog Deer in their surroundings. It was also noted that this species of deer is well known to local inhabitants in the study area, under different vernacular names. Local people of the area were of the opinion that the Hog Deer population had depleted over the last two to three years, due to illegal hunting taking its toll on the species.

This species of Cervidea was also found to occur in both natural or semi-natural forests as well as agro-forest lands particularly the lands of cinnamon plantations. It was found to co-occur with Spotted Deer and Yellow-striped Mouse Deer Moschiola kathygre a much smaller species that is found throughout the study area.

Discussion and Conclusion

As per the present study, it is evident that the distribution of the Hog Deer has increased, covering a much wider area (Fig. 3) than was documented in 1992 by McCarthy and Dissanayake. During the present study the core area used by Hog Deer is one of the biggest areas habouring cinnamon plantations on the island i.e., Karandeniya, Uragasmanhandiya, the Madu River area, Kurudugahahethekma, Batapola Goonapinuwala, Eta-Kotte and Nugethota in the southern catchment of the Benthara River and the northern catchment of the Gin Ganga, these areas belong to two administrative districts namely Kaluthara and Galle. These two districts together harbour 26% of the total forest cover of the island (IUCN Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources 2007). These river basins harbor suitable habitat for the Hog Deer to survive, viz., marshes and riverine forest. As such this area is the last foot hold of the Hog Deer in Sri Lanka, rather than the more densely populated area of the southern catchment of the Kalu Ganga.

Most of the local communities in the area are aware of the presence of Hog Deer in and around their cinnamon plantations and consider this species a pest, due to the damage it causes to their plantations by feeding on the tender leaves of cinnamon, hence the local peoples’ perception that the staple food of this species is cinnamon. It is killed whenever encountered by them, though according to the FFPO (Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance) of Sri Lanka, the Hog Deer is a protected species even though the wanton killing continues, pushing this animal ever close to extinction in its natural habitat (Anonymous 2009). Consequent to all these threats 60% of the local people interviewed stressed the fact that they had noticed a considerable decline in the Hog Deer population within the last few years, and they were of the opinion that due to the clearing of forest and other suitable land for development projects had displaced the Hog Deer putting them to further jeopardy.

During the study, this species was hardly encountered in herds, only on two occasions was it seen in herds, that too, were not in very large ones, only consisting of five individuals or less which consisted of females and fawns. This is smaller in herd size but similar to the basic social groups found in Royal Chithwan National Park, Nepal.(Dhungel & O’gara 1991).

However, it is essential to study the density, home range and other ecological aspects in order to get a precise consensus of the population status. It was also noted, that the male Hog Deer were rarely encountered, during the whole survey only one male was met with, it could be due to the fact that since males lead a solitary life and only form herds during the rutting season (Prasanai et al. 2012) or perhaps they are hunted for their antlers. Given the elusiveness of the species it is very difficult to carry out a census of the population. Despite all, it is clear that several relic populations of Hog Deer inhabit the Bentota and Gin River catchment areas.

Despite being a protected species under the fauna and flora protection ordinance revised Act No.22 of 2009, the illegal killing of these animals continue. The people have several methods of hunting them: one is by night using flash lights, where when the flash light is flashed at the animal it stops in its path and stares at the light making it easy to be shot; the other method is administrated during the day, by using dogs and beaters, where likely forest patches that Hog Deer might be found lying up for the day are disturbed using beaters and when the deer take flight the dogs are set on them and once the animal is cornered it is killed by people. Hog Deer also fall victim to snares and pit fall traps, which are set up for other animals such as wild boar, porcupines this type of hunting has also been highlighted by Philips (1935). However, some animals escape with injuries during the ordeal, hence the high number of animals found with broken legs, damaged ribs during the survey. The victims of this type of hunting are mainly females and fawns as they are found congregating in small herds, and also the villagers tend to target young animals to mature ones as the flesh of the young animals is supposed to be a delicacy (Table 1).

During the survey nine animals were seen in captivity, in places such as monasteries and hermitages, this could have a dire effect on the species as they could interbreed with other species of deer, having a negative effect on their gene pool. Phillips (1935) stresses the fact, that in India this species has interbred with Spotted Deer and have borne fertile young, so if the individuals which are held in captivity do happen to interbreed with Axis Deer, this will definitely have a negative impact on Sri Lanka’s population of Hog Deer. As there is some controversy to the exact status of the Hog Deer, some say that the species was introduced to Sri Lanka during the Dutch colonial period in the early part of the 1500s as a game animal, but taking into consideration the Hog Deer distribution in adjoining South Asian countries (Azam et al. 2002), it is highly unlikely that the Hog Deer was introduced to Sri Lanka during the stipulated period. However, to justify such a notion, genetic studies will have to be carried out on Hog Deer remains found in ancient excavation sites, as well as living individuals to clarify the doubt.

Compared to other species of deer found on the island the Hog Deer is found in highly populated areas, but goes unnoticed, since it sticks to forest patches and cinnamon plantations. During the harvesting season, as the cinnamon plots are cleared, these animals are displaced putting them into dire straits. The conservation of these animals is equally important for the future existence of the species. Well planned translocation porgrammes can be an effective method in conserving the species; such programmes have been initiated for the displaced animals in the Galle District by the Department of Wildlife Conservation. At the same time it is worth taking necessary steps to control and monitor the issues of licensed fire arms to plantation owners in doing so it could minimize the threat by manifold to the Hog Deer.

The clearing of forest reserves for the massive development project of the southern high way, which runs through the strong hold of the Hog Deer, has badly affected the animals, displacing it from its home range and pushing them to occupy isolated patches of forest and cinnamon plantations in adjoining areas. It is proposed that necessary steps be taken in building animal tunnels or corridors in suitable places to facilitate the movement of animals from one side to another. As clustering, isolated populations of Hog Deer could also have a negative impact on their gene pool by diluting it due to too much inbreeding.

In addition to these the foundation for the conservation of this small ungulate should be laid through proper environment education programmes aimed at school children and community groups.

Recommendations

- To carry out studies using camera traps, this would shed light on its population density, distribution and population structure.

- Carrying out of a long-term ecological study on Hog Deer in its current distributional limits covering population status, group structure and composition, food and feeding, so that consensus could be made in developing conservation action plans.

- To carry out genetic studies on the population to determine its heterozygosity level to see whether the population is inbred.

- To declare a protected area in the core area occupied by Hog Deer.

References

Anonymous (2005). Indian Wildlife. Deer: Hog Deer. <http://iloveindia.com/wildlife/india-wild-animals/deer/hog-deer.html>. Downloaded on 03 August 2008.

Anonymous (2007). Identification of Feral Deer in South Australia. Government of South Australia. South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resource Management Board.

Anonymous (2008). The Deer Initiative. Dung Counting. <www.thedeerinitiative.co.uk> Downloaded on 01 December 2008.

Anonymous (2009). Government Gazette of “A revised Act No 22 of Fauna and Flora Protection Sri Lanka.

Azam, M.M., S.A. Khan & S. Qamar (2002). Distribution and population of Hog Deer in district Sandhar, Sindh. Records Zoological Survey of Pakistan 14: 5–10.

Dhungel, S.K. & B.W. O’Gara (1991). The ecology of the Hog Deer in Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Wildlife Monographs (119): 1–4.

IUCN Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (2007), The 2007 Red Lanka”. List of threatened Fauna and Flora of Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka, XIII+148pp.

Keneth, N.R. (2005). Questionnaire design. Quantitative research methods in education planning. UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning.

McCarthy, A.J. & S.B. Dissanayake (1994). Status of Hog Deer in Sri Lanka. Oryx 28(1): 62–66.

Phillips, W.W.A. (1935). Manual of the Mammals of Ceylon. 2nd Edition reprinted in 1984. Wildlife and Nature Protection Society Sri Lanka, 389pp.

Pocock, R.I. (1943). The larger deer of British India. Part IV. The Chital (Axis) and the Hog-deer (Hyelaphus). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 44: 169–178.

Prasanai, K., R. Sukmasuang, N. Bhumpakphan, W. Wajjwalku & K. Nittaya (2012). Population characteristics and viability of the introduced Hog Deer (Axis porcinus) Zimmermann, 1780) in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand. Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology 34(3): 263–271.

Sutherland, W.J. (1996). Ecological Census Techniques. Cambridge University press, UK, 337pp.

Yapa, A.C. & G. Ratnavira (2013). The Mammals of Sri Lanka. Field Ornithology Group, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1012pp.