Human-crocodile conflict and conservation implications of Saltwater Crocodiles Crocodylus porosus (Reptilia: Crocodylia: Crocodylidae) in Sri Lanka

A.A. Thasun Amarasinghe 1, Majintha B. Madawala 2, D.M.S. Suranjan Karunarathna 3, S. Charlie Manolis 4, Anslem de Silva 5 & Ralf Sommerlad 6

1 Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Gd. PAU Lt. 8.5, Kampus UI, Depok 16424, Indonesia

2 South Australian Herpetology Group, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia

3 Nature Explorations & Education Team, No. B-1/G-6, De Soysapura Housing Scheme, Moratuwa 10400, Sri Lanka

4 Wildlife Management International, PO Box 530, Karama, NT 0813, Australia

5 No. 15/1, Dolosbage Road, Gampola, Sri Lanka

6 Crocodile Conservation Services Europe, RoedelheimerLandstrasse 42, Frankfurt 60487, Germany

1 thasun@rccc.ui.ac.id (corresponding author), 2 majintham@yahoo.com, 3 dmsameera@gmail.com, 4 cmanolis@wmi.com.au, 5 kalds@sltnet.lk, 6 crocodilians@web.de

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o4159.7111-30

Editor: B.C. Choudhury [Retd.], Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India. Date of publication: 26 April 2015 (online & print)

Manuscript details: Ms # o4159 | Received 26 September 2014 | Final received 26 February 2015 | Finally accepted 27 March 2015

Citation: Amarasinghe, A.A.T., M.B. Madawala, D.M.S.S. Karunarathna, S.C. Manolis, A. de Silva & R. Sommerlad (2015). Human-crocodile conflict and conservation implications of Saltwater Crocodiles Crocodylus porosus (Reptilia: Crocodylia: Crocodylidae) in Sri Lanka. Journal of Threatened Taxa 7(5): 7111–7130; http://dx.doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o4159.7111-30

Copyright: © Amarasinghe et al. 2015. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. JoTT allows unrestricted use of this article in any medium, reproduction and distribution by providing adequate credit to the authors and the source of publication.

Funding: Self funding of AATA, MBM, and DMSSK

Competing Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Author Contribution: AATA, MBM, and DMSSK conceived the concept, ideas, plan of work and did field work; AATA prepared the maps and manuscript; AdS and RS contributed data and improved the manuscript; CM helped with preparing the manuscript and final editing.

Author Details: All the authors are commission members of the Crocodile Specialist Group (CSG), Species Survival Commission (SSC), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Acknowledgements: We thank Colin Groves, Mohamed Bahir and other anonymous reviewers who critically reviewed this manuscript and helped improve the quality; Special acknowledgement to the field survey team for their assistance in the field. Then we would like to thank many national park rangers and safari guides, safari jeep drivers in Udawalwa, Yala and Bundala National Parks for providing all the translocation details and help to locate animals inside national parks, villagers in study areas for providing information, and safari jeep owners for providing transportation to visit national parks and locate the translocated crocodiles. Finally, we would like to thank members of the Young Zoologists’ Association (YZA) for their support; A. Godahewa, J. Ranasinghe and P.D. Weeraratne for photographs.

Abstract: Human-wildlife conflict occurs when human requirements encroach on those of wildlife populations, with potential costs to both humans and wild animals. As top predators in most inland waters, crocodilians are involved in human-wildlife conflicts in many countries. Here we present findings of a 5-year survey on human-crocodile conflict on the island of Sri Lanka and relate the results to improving management practices. We aimed to quantify and understand the causes of human-crocodile conflict in Sri Lanka, and propose solutions to mitigate it. Visual encounter surveys were carried out to estimate the population size of Saltwater Crocodiles. We recorded 778 sightings of Saltwater Crocodiles at 262 of 400 locations surveyed, and estimate the total population to comprise more than 2000 non-hatchlings and to have increased at an average rate of 5% p.a. since 1978. We propose four crocodile vigilance zones within the wet zone and one crocodile vigilance zone within the dry zone of the country. Specific threats to Saltwater Crocodiles identified in crocodile vigilance zones were: habitat destruction and loss; illegal killing and harvesting (17 killings out of fear, ~200 incidents of killing for meat and skins, ~800 eggs annually for consumption); unplanned translocations; and, interaction with urbanization (10 incidents of crocodiles being run over by trains/vehicles and electrocution). Additionally, 33 cases of crocodile attacks on humans were recorded [8 fatal, 25 non-fatal (minor to grievous injuries)] and more than 50 incidents of attacks on farm and pet animals.

Keywords: habitat loss, hunting, road kills, policy and planning, translocation, crocodile vigilance zones

Introduction

Human-wildlife conflict is a growing issue worldwide (Woodroffe et al. 2005) and crocodilians are one of the major groups involved (Lamarque et al. 2009). Sri Lanka is a relatively small island of approximately 65,500km2, but home to large populations of crocodiles and other large wild animals (e.g., elephants, leopards, sloth bears, etc.), as well as humans. The human population density in Sri Lanka’s biologically richest wet zone (southwest), is one of the highest on earth (Cincotta et al. 2000), and is growing more rapidly around protected areas (Wittemyer et al. 2008) and in developing coastal cities such as Colombo, Negombo, Galle, Matara, and Hambantota. As a result, human-crocodile conflict (HCC) is increasing.

Two allopatric species of crocodiles occur in Sri Lanka; the Mugger Crocodile, Crocodylus palustris Lesson, 1831, and the Saltwater or Estuarine Crocodile, Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801 (Deraniyagala 1939). The Saltwater Crocodile is the largest living reptile on Earth; it can grow up to 6–7 m (Webb et al. 1978; Whitaker & Whitaker 2008; Erickson et al. 2012). Like other crocodilians it is an opportunistic feeder, using active hunting or ‘sit and wait’ strategies (Cooper & Jenkins 1993), and the frequency of different prey items varies significantly with habitat and body size (Taylor 1979; Webb & Manolis 1989). Although telemetry studies are increasing our knowledge of movement patterns and extent of home ranges for Saltwater Crocodiles (e.g., Webb & Messel 1978; Kay 2004; Read et al. 2007; Brien et al. 2008; Campbell et al. 2013, 2014; Hanson et al. 2014), which can assist management efforts, there is still a paucity of information for most range states for the species, including Sri Lanka.

Saltwater Crocodiles are distributed in a wide variety of saline and freshwater habitats, including rivers and creeks, coastlines, coastal flood plains, lagoons, swamps, river and canal outfalls (e.g., see Webb & Manolis 1989; & ). Although popularly referred to as ‘salties’ in Sri Lanka, a high proportion of the Saltwater Crocodile population exists in freshwater habitats in the western and southern parts of the country (e.g., Nilwala, Bentota, Kelani, Maha Oya; de Silva 2013), including Colombo, the capital (Devapriya 2004; Jayawardene 2004; Porej 2004; Samarasinghe 2014).

Under Sri Lankan legislation the Saltwater Crocodile is listed as ‘endangered’ (MOE 2012). In the 1970s, Whitaker & Whitaker (1977, 1979), urged the Sri Lankan Government to establish a sanctuary in which Saltwater Crocodiles would be protected and could live without conflict with humans. In reality the species has received “paper protection” (Whitaker 2004), with the responsible wildlife authority, the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), handling crocodile issues without sufficient bio-geographical, taxonomic, behavioural or ecological understanding of the species. Some management measures, such as the translocation of ‘problem’ crocodiles, have ended with critical arguments, media debates, and dead or disappeared crocodiles.

This publication aims at quantifying and understanding the causes of HCC in Sri Lanka, and proposes solutions to mitigate it. We also provide new insights into the social and biological context in which crocodile conservation and management programs could operate in Sri Lanka.

Materials and methods

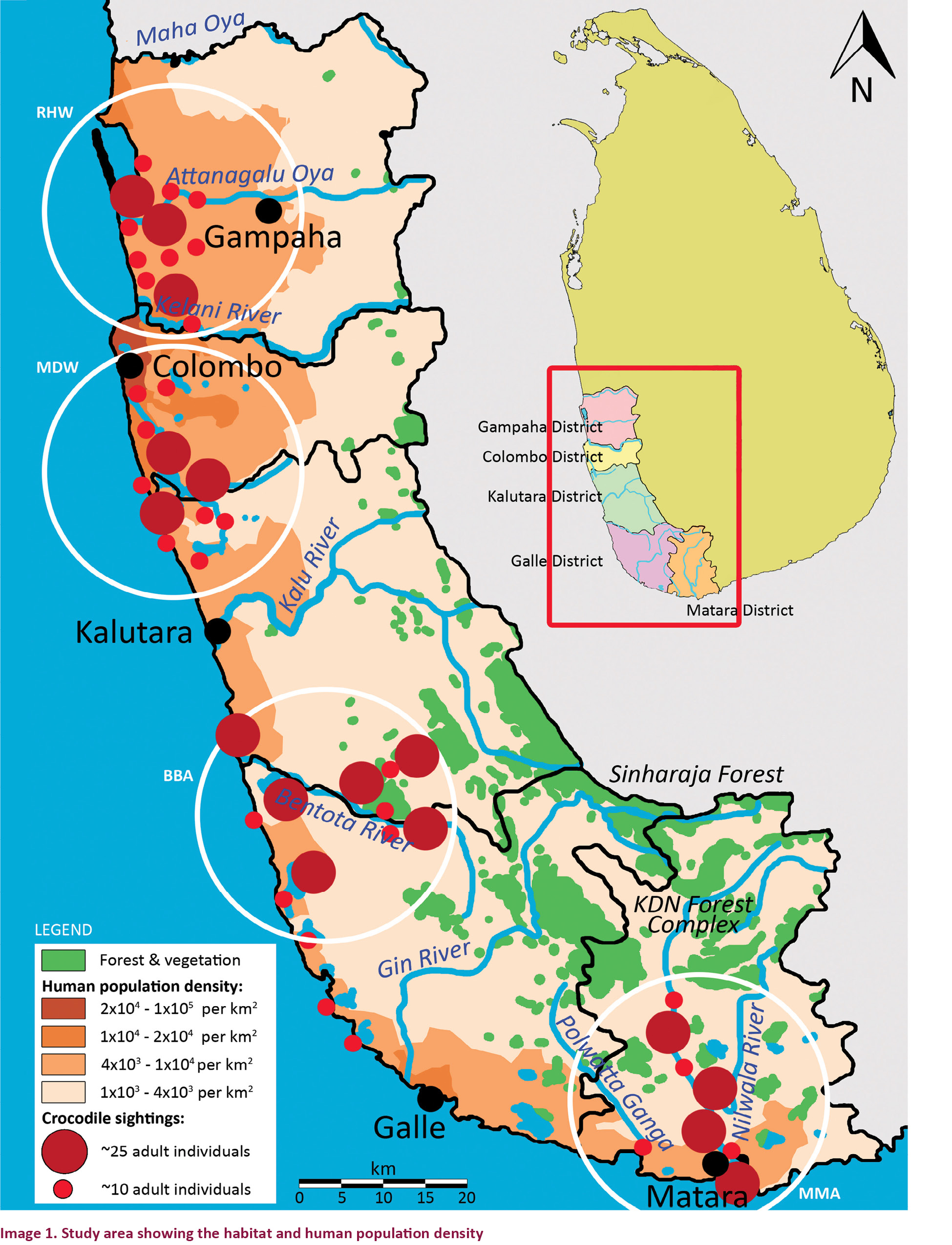

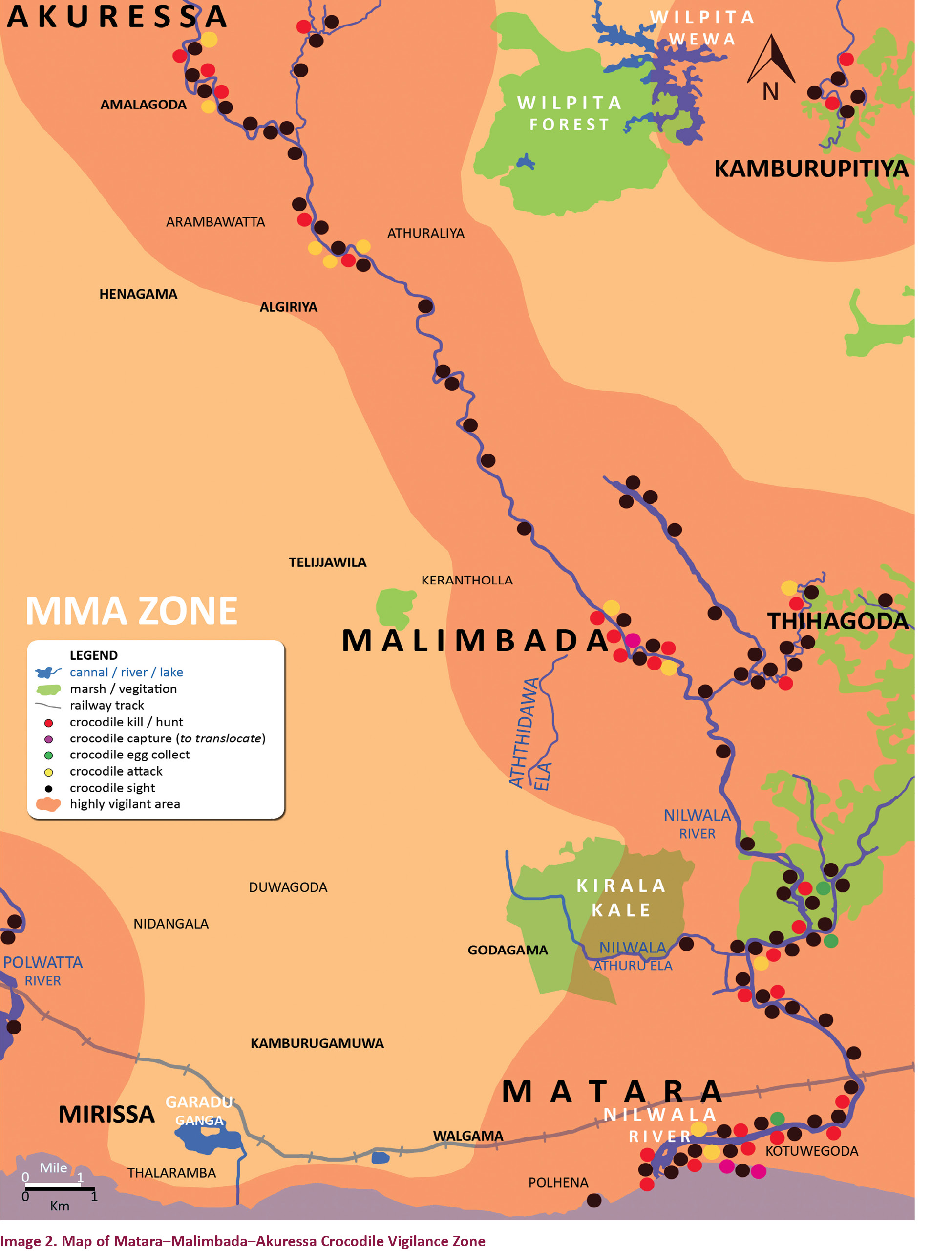

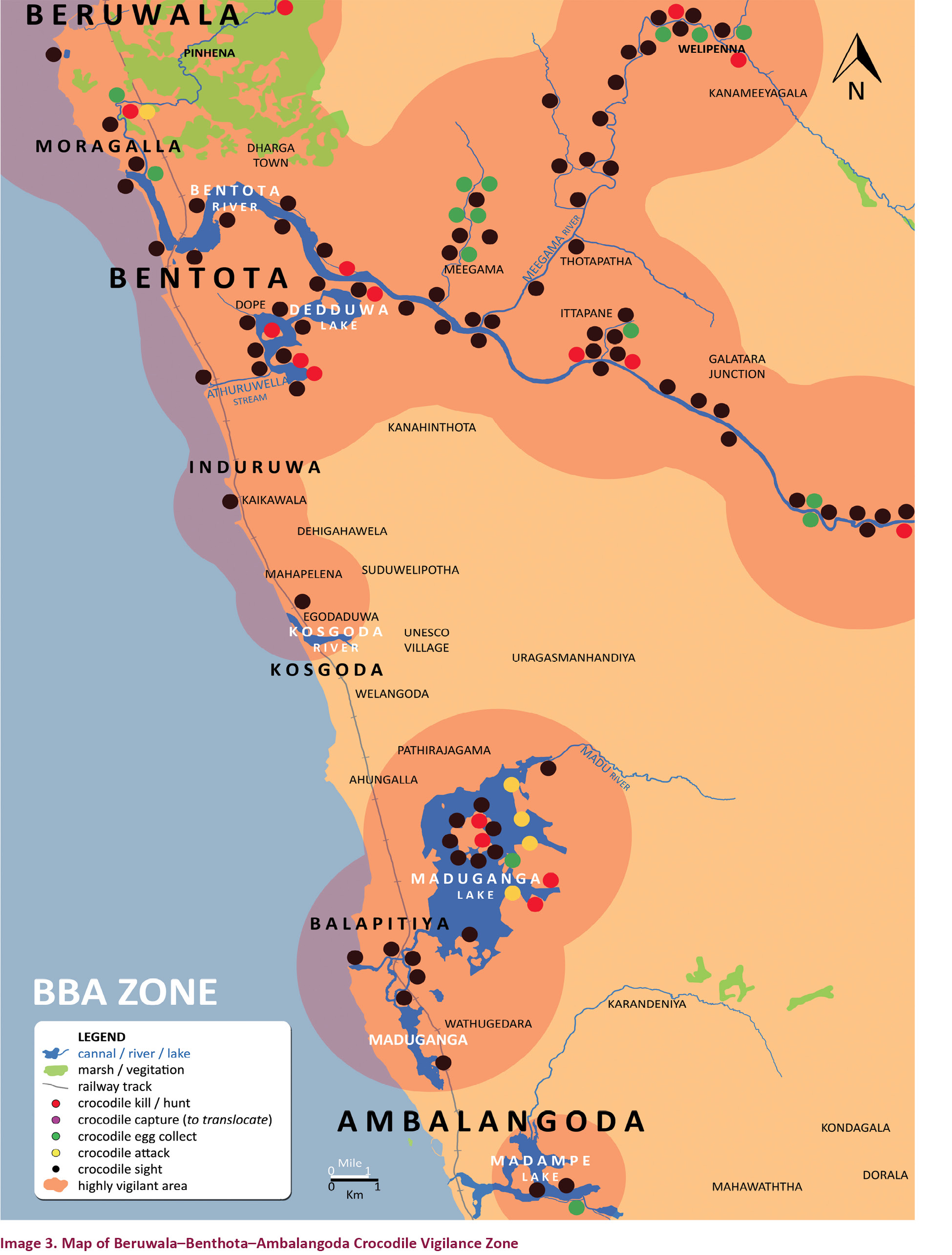

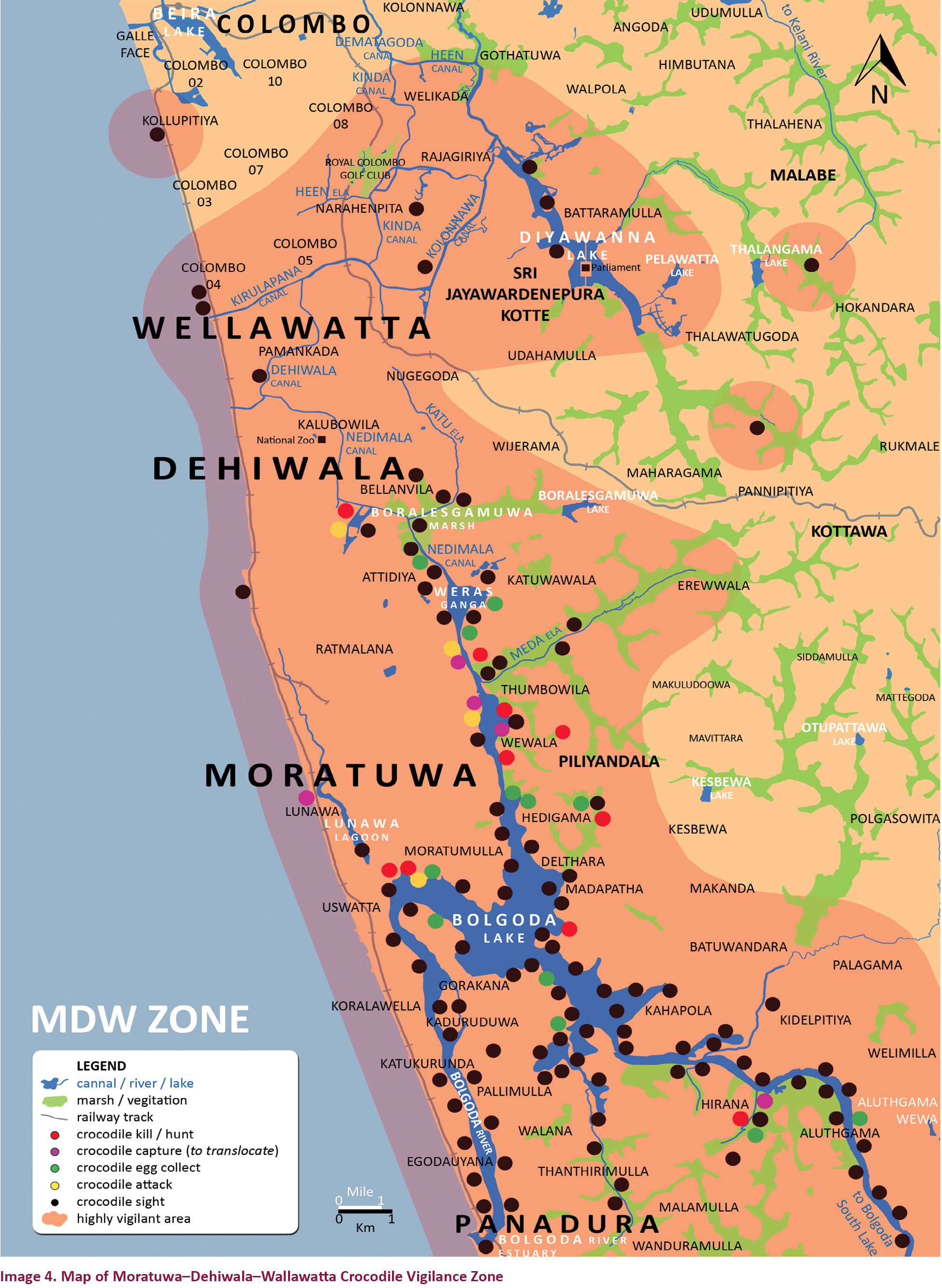

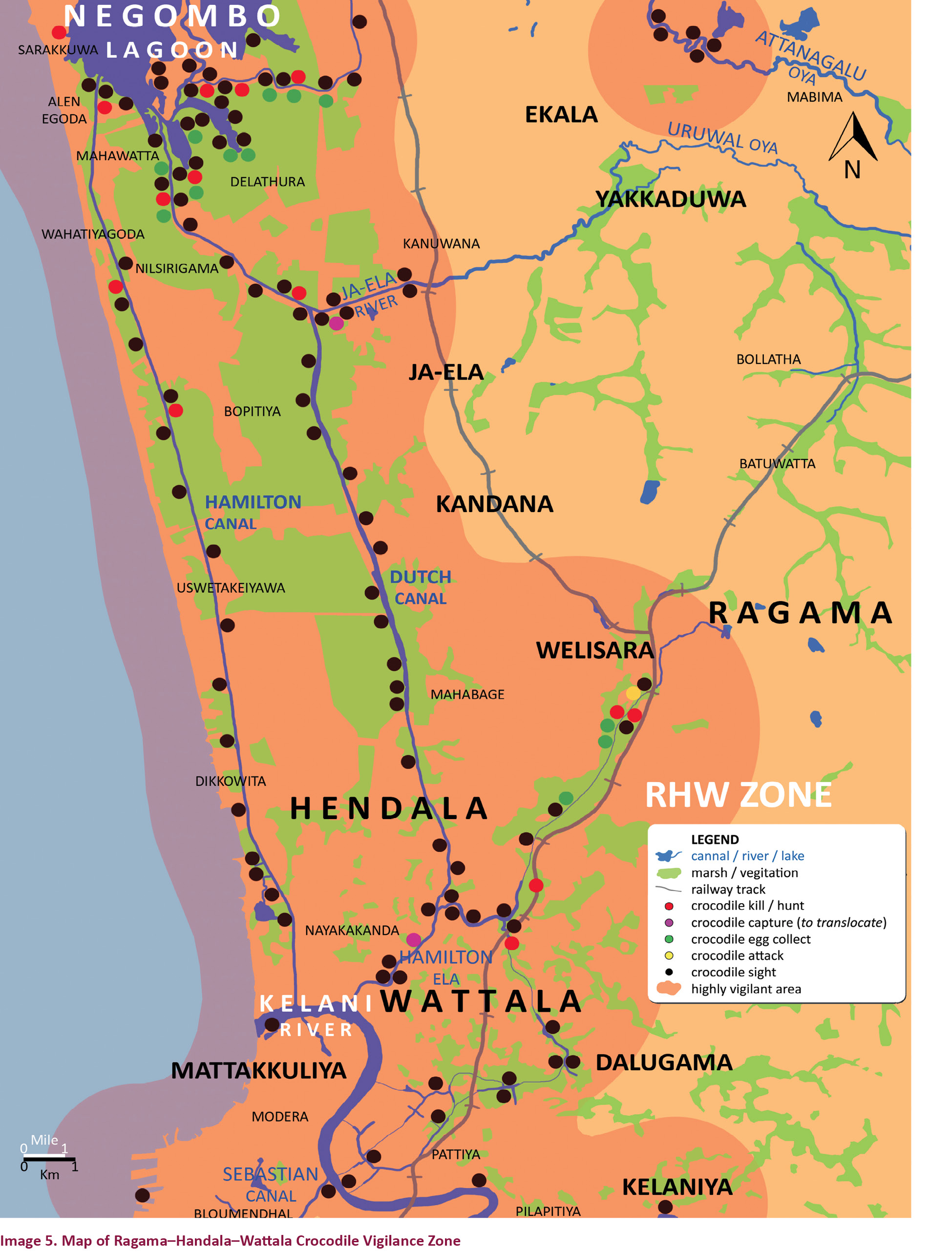

Between January 2008 and December 2012 we visited 400 locations within Gampaha, Colombo, Kalutara, Galle and Matara Districts in the ‘wet zone’ of the country (Image 1), including beaches from Negombo on the west coast to Matara on the south coast. We divided specific survey areas in the wet zone into four regions (Images 2–5). Systematic surveys in the dry zone could not be carried out due to civil unrest, but some sightings of Saltwater Crocodiles were recorded during general visits to some parts of the area.

Spotlight and daytime surveys were carried out from boats in rivers, lagoons and other large water bodies, and we supplemented these counts with other personal observations (both day and night) along small streams and canals, marshes, and other small water bodies. We approached crocodiles that were sighted, as close as possible to confirm the species and to estimate their size. All spotlight survey sightings were recorded as “eyes only”.

Each region was surveyed during different time periods (January 2008–March 2009; April 2009–June 2010; July 2010–September 2011; and October 2011–December 2012). In all, approximately 500 kilometers were surveyed during the 5-year period, representing around 75% of the available habitat for Saltwater Crocodiles.

We also examined several Saltwater Crocodiles that had been captured by villagers, unknown groups and wildlife authorities. We photographed color patterns on the flanks and tails of these animals, and other characteristics (e.g., body size, amputations) were noted for future identification. These crocodiles were translocated by the wildlife authorities to national parks. After translocation, we attempted to ascertain the fate of the animals through direct observation [e.g. using binoculars (7x50) from jeeps]. Anand et al. (2013) reported that 16 crocodiles (14M: 2F) were captured and translocated to inland water bodies and to Muthurajawela (in Colombo). These animals were not responsible for attacks on people, and as we could not observe them post-release, they were not included in our analysis.

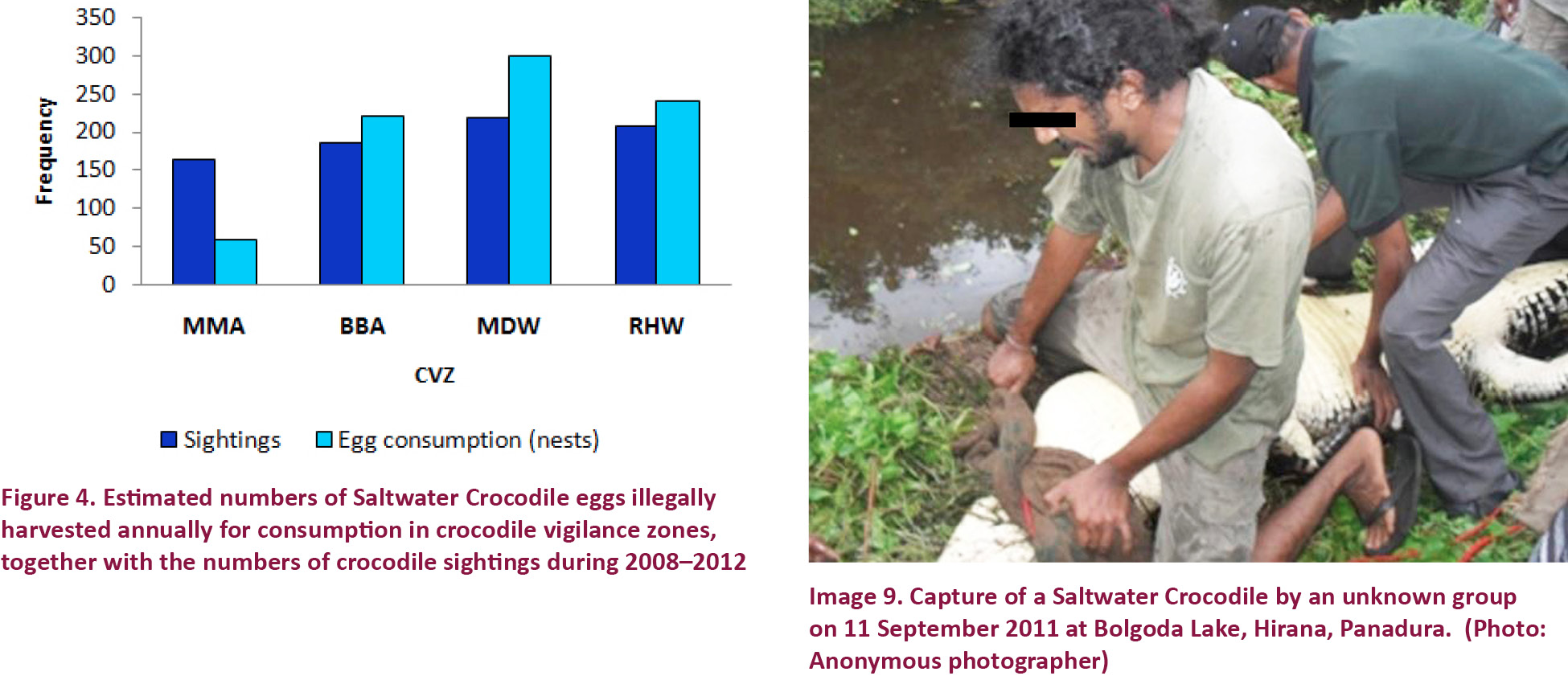

We interviewed people living around the crocodile capture locations to identify the extent of HCC. On the basis of the survey and interview results we identified zones of high HCC incidence involving Saltwater Crocodiles within the survey regions, which we refer to as “Crocodile Vigilance Zones” (CVZ): RHW - Ragama-Hendala-Wattala; MDW - Moratuwa-Dehiwala-Wellawatta; BBA - Beruwala-Bentota-Ambalangoda; MMA - Matara-Malimbada-Akuressa.

Results

Crocodile population

We recorded 778 sightings of Saltwater Crocodiles within 262 of the 400 sites visited. The majority of sightings were recorded during the day (82.5%), and the remainder from spotlight surveys (17.5%). We estimate that 25 crocodiles counted during daytime surveys were re-counted during spotlight surveys, and 98 sightings were hatchlings (<60cm total length).

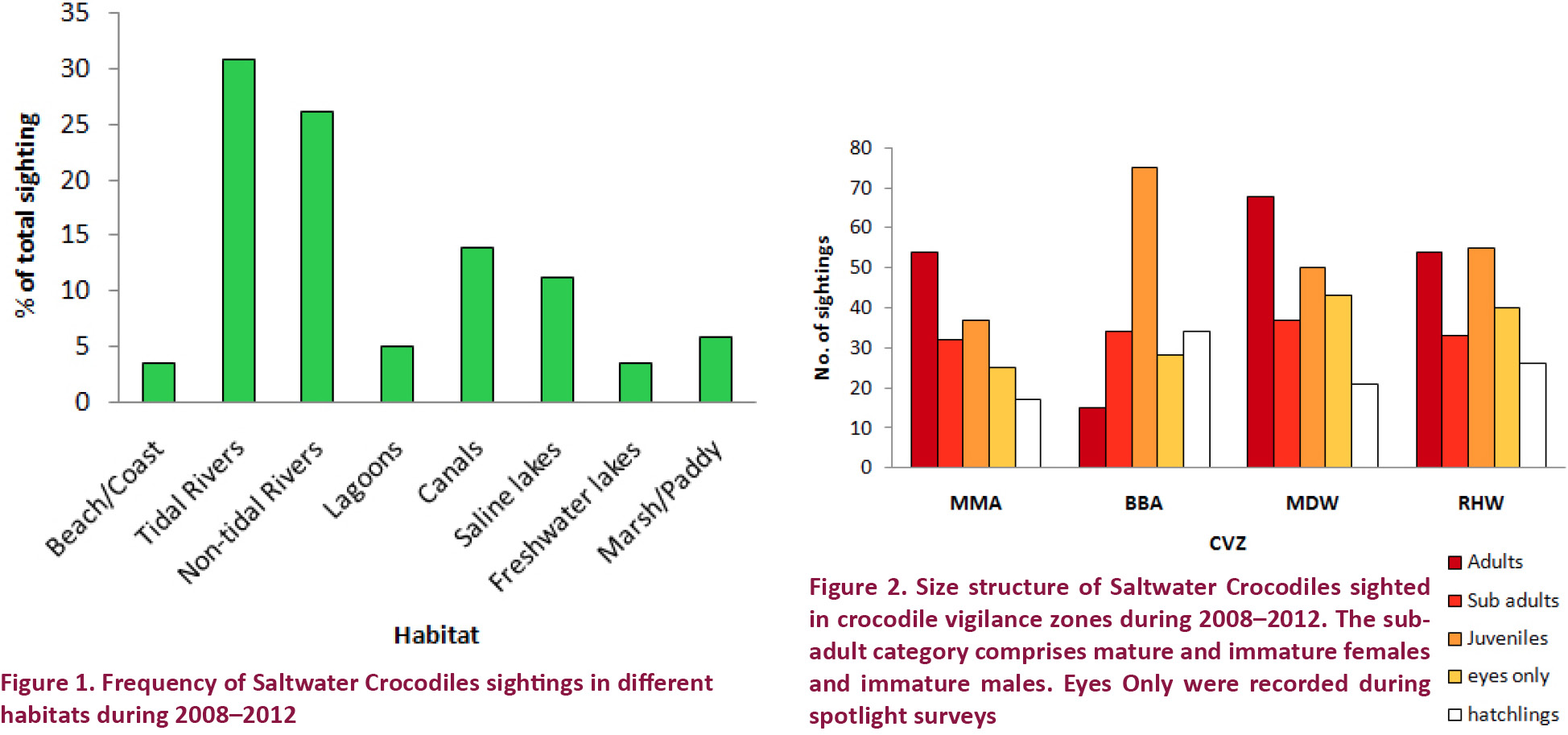

Most (64%) of the sightings were from the Nilwala River basin (140, 18%); Bentota and Meegama river basins (102, 13%); Dutch-Hamilton Canals and Ja-Ela River (106, 13%); and the Bolgoda River and Lake (154, 20%). We also observed Saltwater Crocodiles in the sea or on the seashore at Matara, Beruwala, Bentota, Induruwa, Balapitiya, Kollupitiya, Bambalapitiya, Dehiwala, and Ratmalana. A higher proportion of sightings (57%) were recorded from tidal and non-tidal rivers, than from the coast and freshwater lakes (Fig. 1).

On the basis of the daytime surveys, where crocodile size estimates were available, juveniles (immature non-hatchlings) comprised an estimated 55–60% of non-hatchling sightings (see Fig. 2). Given that small crocodiles are not as easily sighted as large crocodiles during daytime surveys (Webb et al. 1990), it is likely that juveniles comprise a higher proportion of the population than is indicated by our results. Hatchlings were sighted in each of the survey regions, but the highest numbers were recorded from habitats with well-established vegetation, such as mangroves and riverine forests.

To derive a total population estimate, we excluded hatchlings and the duplicate counts, applied conservative correction factors of 1.59 to spotlight counts and 2.50 to daytime counts (Bayliss et al. 1986; Webb et al. 1990), and applied a correction factor of 1.33 to account for habitat that was not surveyed/visited. The current total population is thus estimated to be at least 2000 non-hatchling Saltwater Crocodiles. Bearing in mind that the correction factors that we used to account for sightability are conservative, and no attempt was made to correct for seasonal biases or annual increases in the population between 2008 and 2014, this estimate is considered to be an underestimate of the real population size.

Interestingly, half of the interviewees who use the water source for daily activities were not aware of the abundance of crocodiles as was observed during the study.

Habitat destruction and loss

The major threats observed for Saltwater Crocodiles in Sri Lanka were: encroachment of human settlements; habitat loss and destruction (draining and refilling of wetlands, conversion of mangroves and coastal habitats for prawn farms, sand extraction, developing tourist hotels (including high intensity lighting), unplanned road/railway constructions); road/rail kills; and, increased fishing activities in the country. In particular, the removal of riverine forests and the reclamation of swamps directly affect Saltwater Crocodile nesting habits and habitats. Many crocodile habitats are surrounded by fishing villages and tourism zones, and the animals in these habitats are potentially impacted by motor boat activity, oil, noises, garbage, polythene, discarded fishing nets, and fishing tools. We observed higher densities of crocodiles around areas where garbage is dumped and which are covered with alien invasive plants - these habitats may be considered as refuge habitats for crocodiles in urban environments. It is possible that crocodiles are attracted to garbage dumps due to the smell of rubbish or other prey items such as rats, birds, dogs, which are attracted to dumped food.

Hunting, other killing, and loss of life

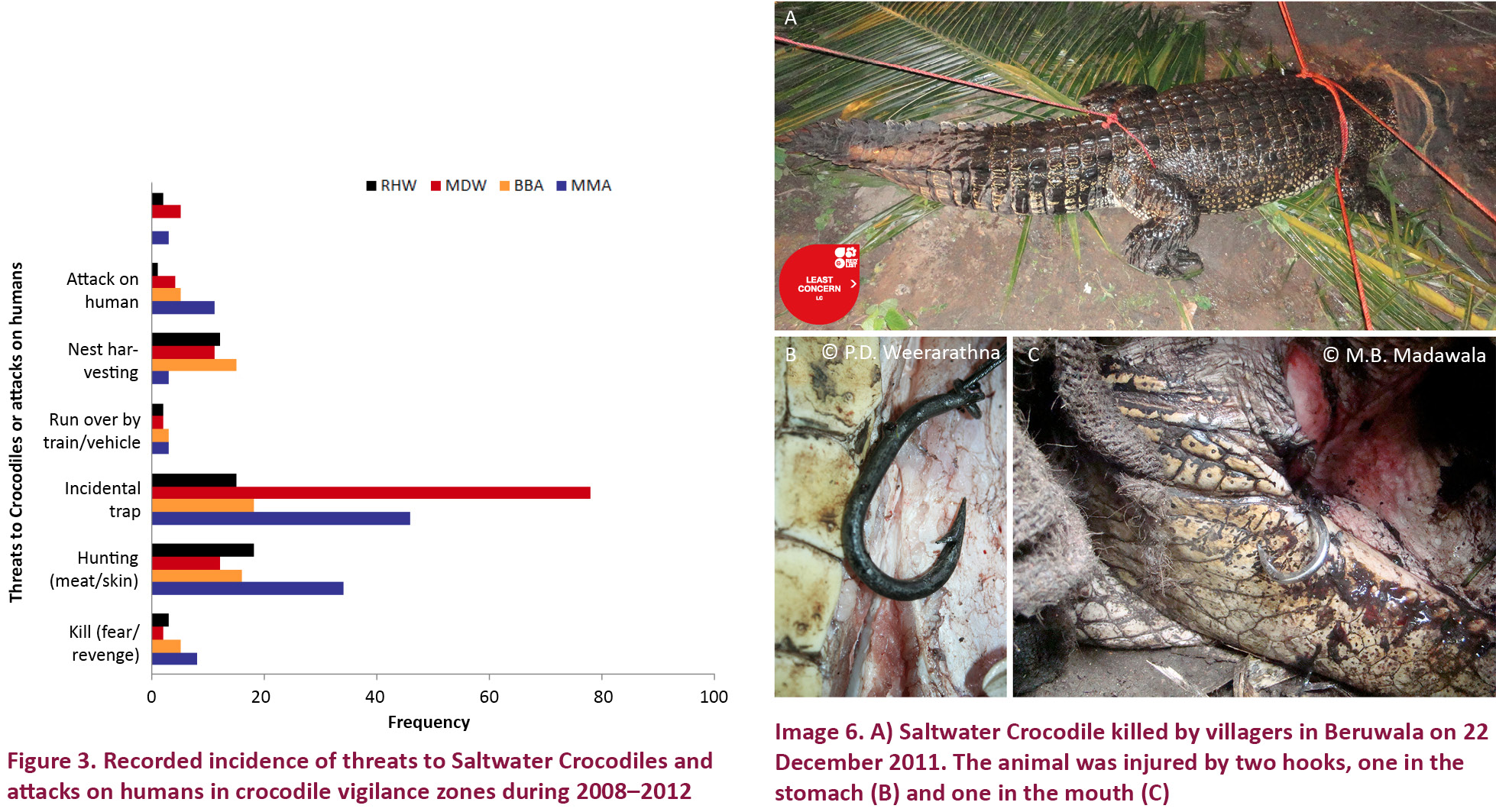

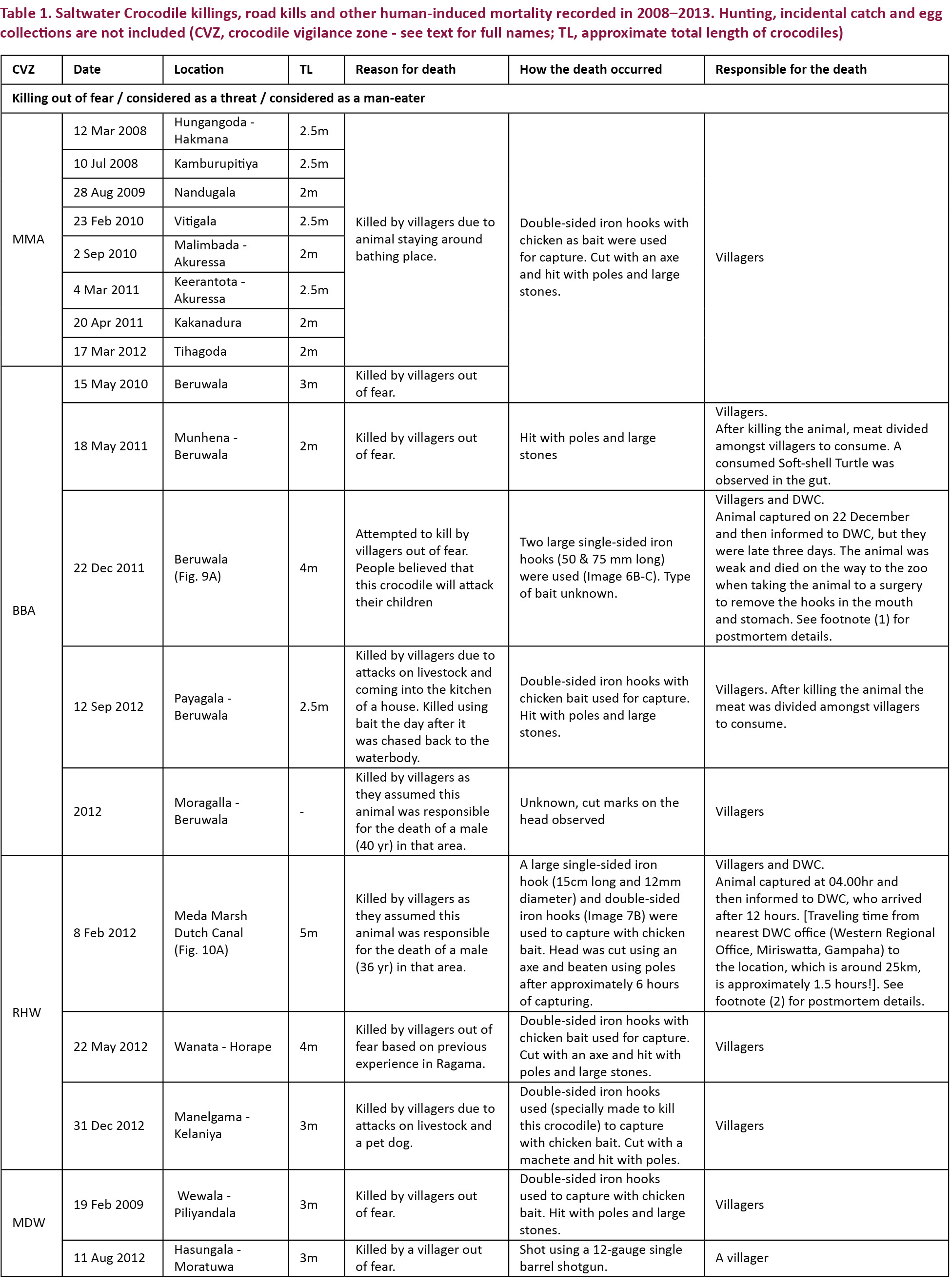

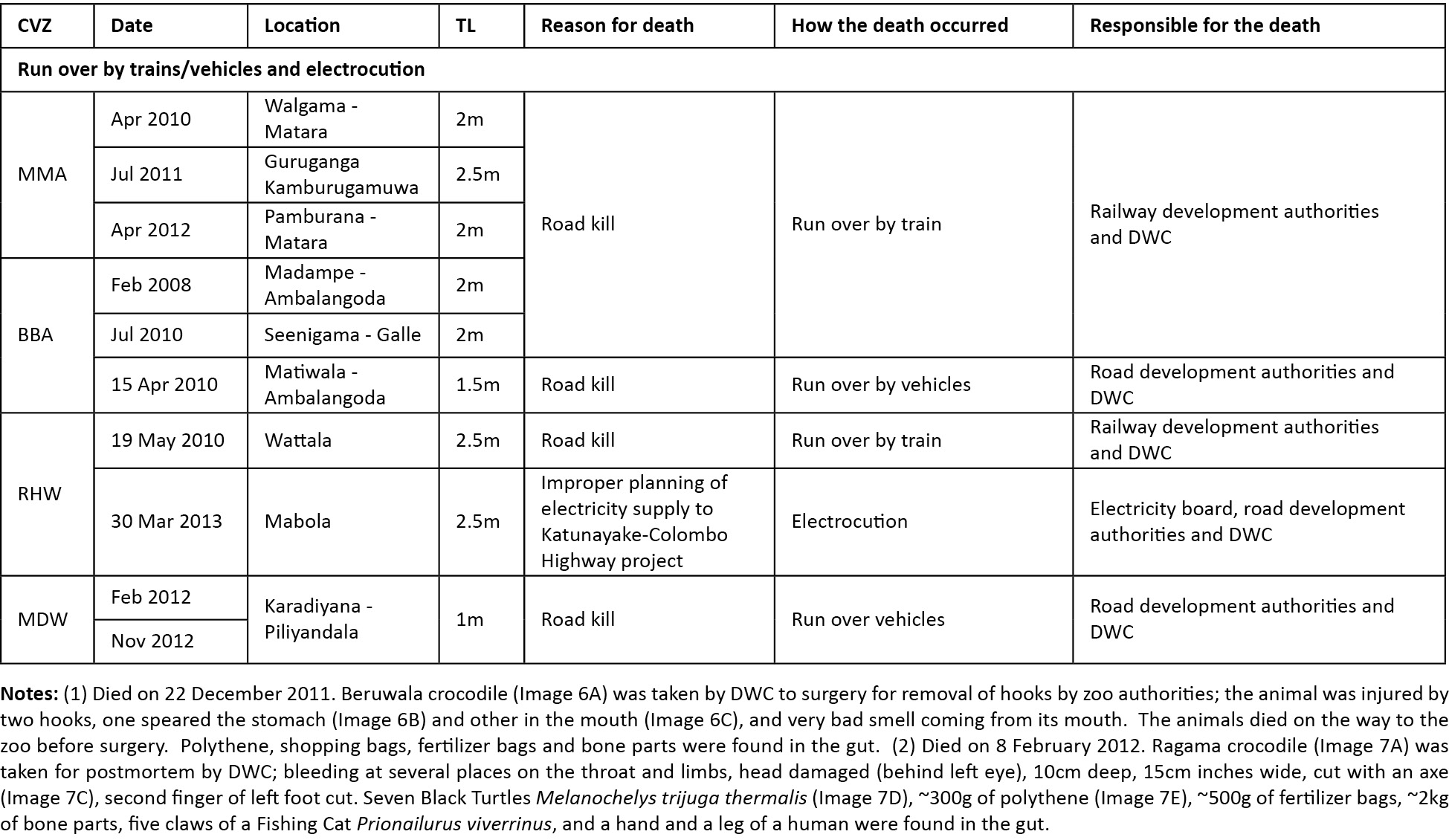

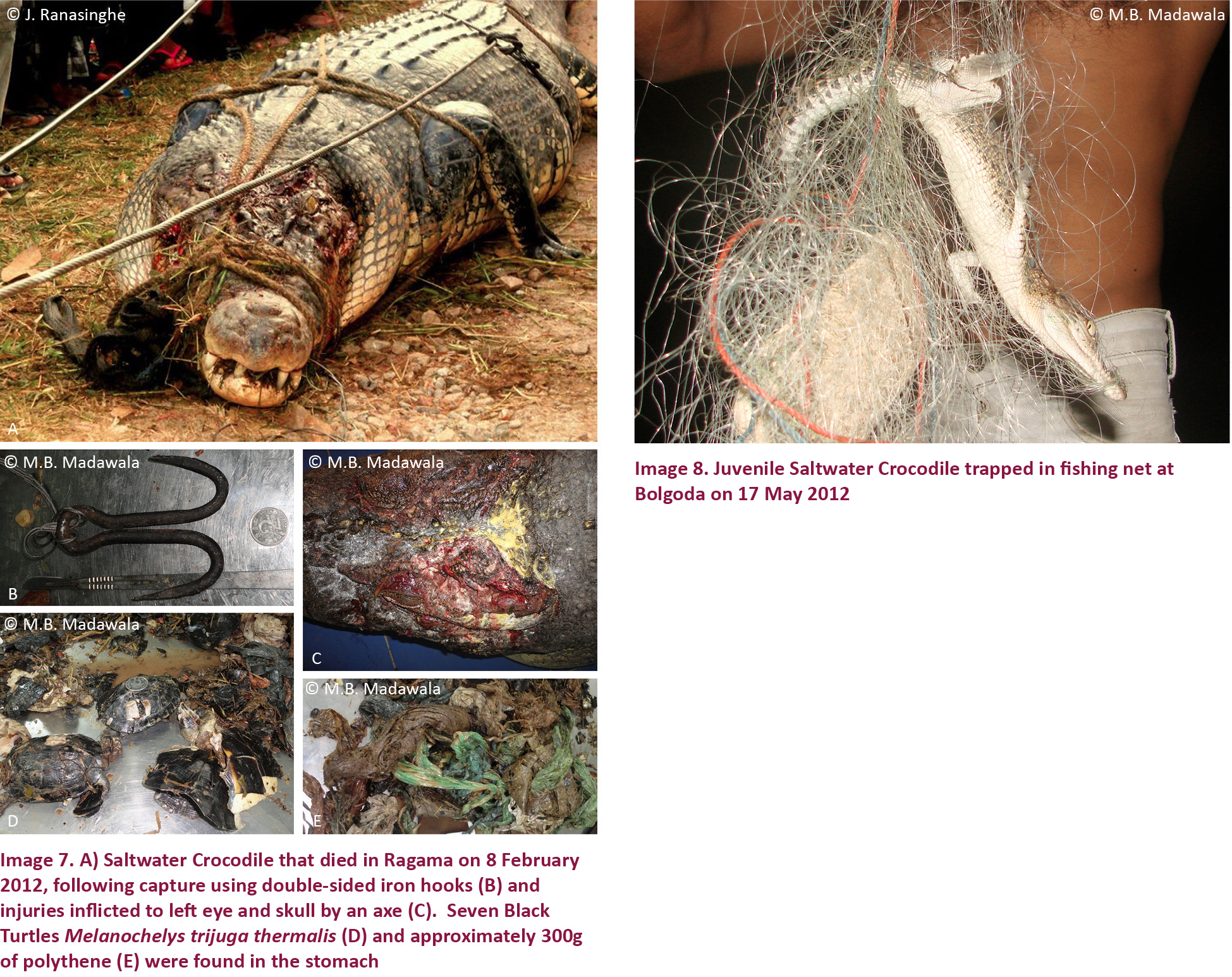

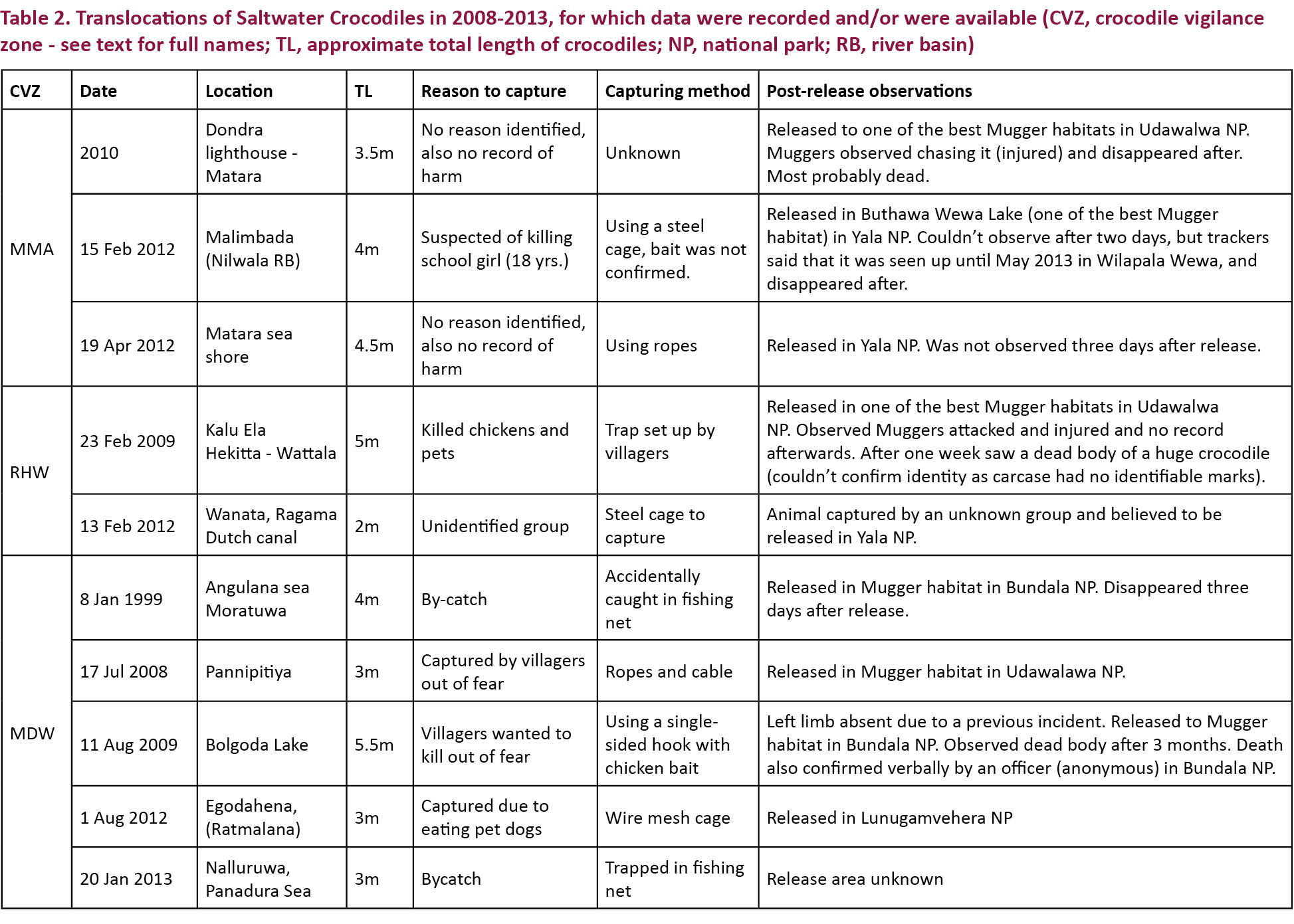

Two-hundred incidents of direct and incidental take of non-hatchling Saltwater Crocodiles were recorded (Fig. 3, Table 1), sometimes as revenge after an attack on family members (or friends), but mainly for meat and skins (Images 6, 7). Juvenile crocodiles (40–120 cm total length) accounted for 80% of the total take, and most (90%) of them were caught incidentally in fishing nets (Fig. 3, Image 8) or prawn traps; the remaining 10% were taken as a result of direct hunting. Even the smallest crocodiles are consumed, after being fried or smoked.

Crocodile meat is sold in surrounding areas and sometimes distributed free amongst neighbours. We observed crocodile meat being mixed together with and sold as shark meat—one kilogram of crocodile meat in the Ragama-Handala-Wattala area sold for 300 Sri Lankan Rupees (approximately $US 2.50), whereas shark meat sells for around 900 Rupees (approximately $US 7.50/kg). While transporting crocodile meat out of an area, hunters use fish containers to hide it from police officers.

Most skins were reportedly purchased by ‘foreigners’, usually after being tanned, but a few are in raw salted form. However, we saw no evidence of products or handicrafts being manufactured from crocodile skin, although such illegal activity may operate covertly.

We estimate that over 800 Saltwater Crocodile eggs (equivalent to around 40 nests) were illegally harvested annually for consumption during the 5-year survey period (Fig. 4). Although the full extent of Saltwater Crocodile nesting is unknown at this time, this level of illegal harvest is considered to involve a high proportion of nests that are produced. We also observed approximately 20 nests that were predated by domestic dogs, Water Monitor Varanus salvator, Land Monitor V. bengalensis, Wild Boar Sus scrofa, Jackal Canis aureus, Python Python molurus, Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala and Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans, and some cases of cannibalism.

Nine crocodiles were run over by trains and other vehicles, and one individual was observed electrocuted in the Ragama area.

Translocations

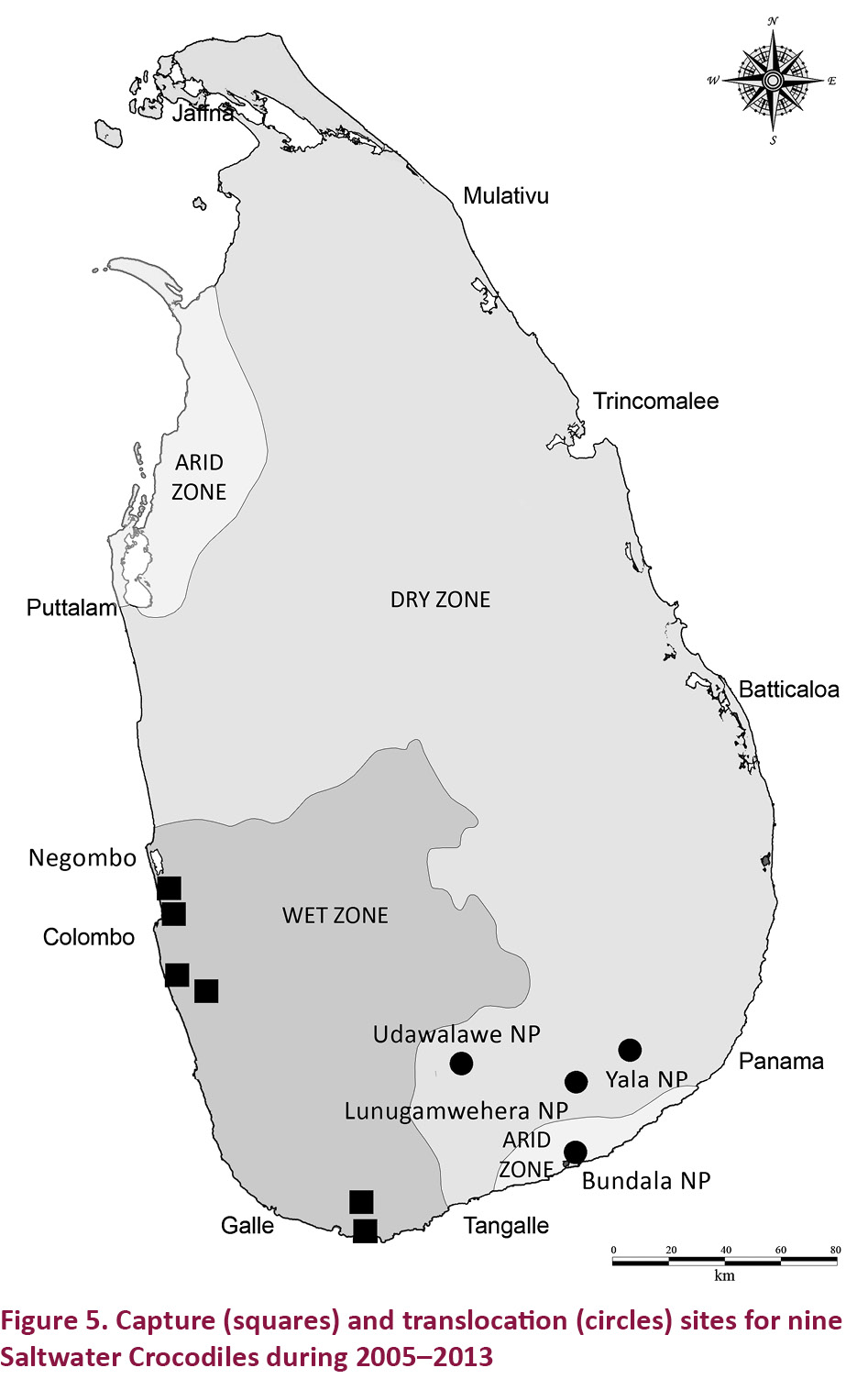

Due to the loss of human life, attacks and general increase in HCC, The Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) started to translocate Saltwater Crocodiles from areas of conflict. Most of the suspected ‘problem’ Saltwater Crocodiles were captured and released into inland freshwater pools which are already heavily populated by Mugger Crocodiles. During the period of this study DWC released crocodiles to inland pools at Udawalawa, Bundala and Yala National Parks (see Fig. 5, Table 2), and recently to Lunugamwehera National Park (after the study).

Field observations since 2000 indicate that Muggers and Saltwater Crocodiles do not share the same wild habitats, except for a few localities where they may overlap seasonally due to the migration patterns of the latter, which are known to move long distances (e.g., Allen 1974; Manolis 2005; Read et al. 2007). For example, the two species are sympatric during some seasons in the estuary of the Walawe River Basin, and a few localities between Tangalle-Hambantota, Yala National Park and Bundala National Park, although the latter two localities could reflect introduced populations resulting from translocation activities.

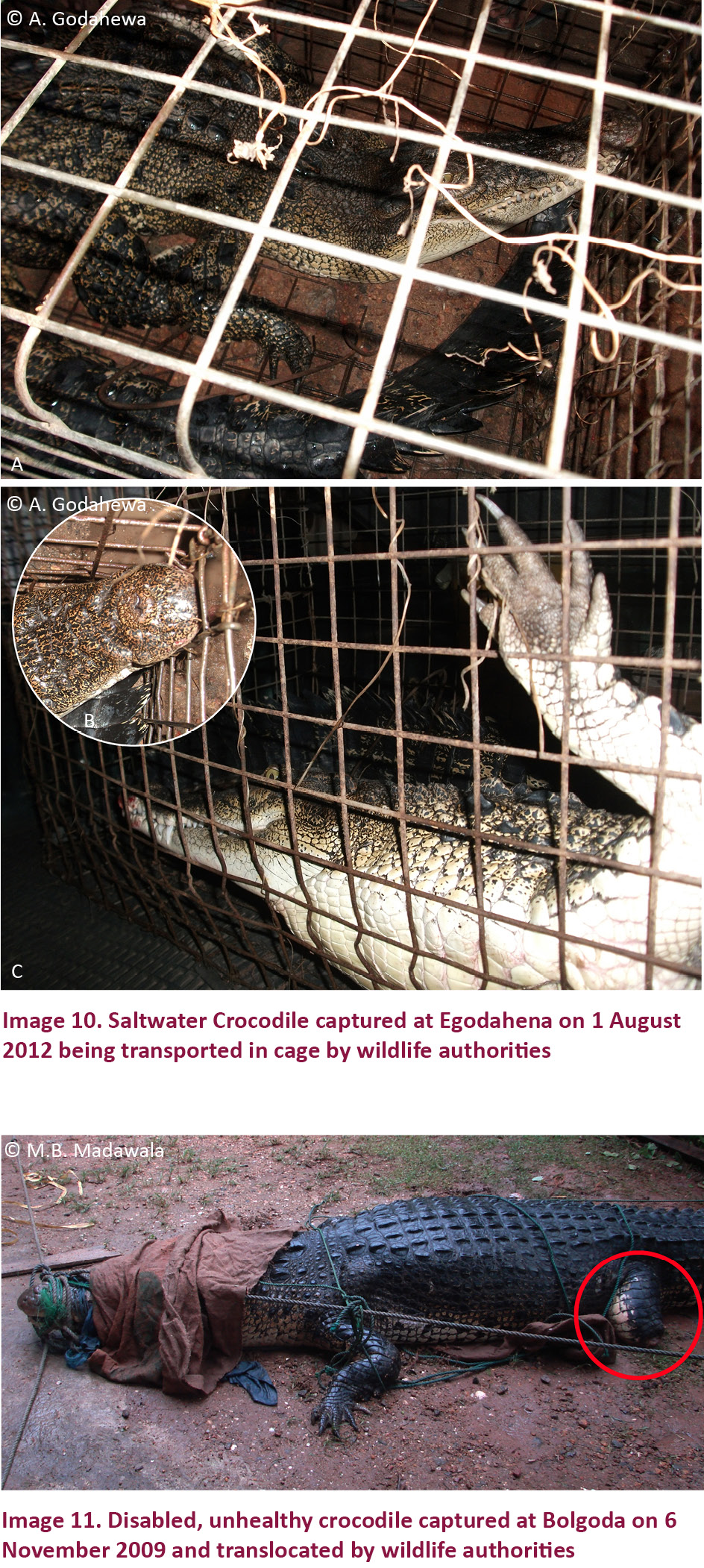

The translocation methods used by DWC and unknown groups (Image 9) are considered unacceptable, as there is a high risk of crocodiles being injured during transportation. The types of enclosure being used are not appropriate for safe translocation (Image 10), and their design should consider the health and well-being of the animals (Image 11). In Yala and Udawalawa national parks we observed that within a few days, for most of translocations, resident Muggers began to attack the introduced Saltwater Crocodiles, which were always ‘defeated’ and/or injured and tried to move to other pools. Interestingly, half of the observed translocations involved Saltwater Crocodiles estimated to be over 4m in length (Table 2), which may have been considered to be able to deal with Muggers, but this was not the case. As almost all pools are utilized by Muggers, the Saltwater Crocodiles had to face the same challenges everywhere, ending with fatal injuries or ‘disappearance’ from our visual observations (Table 2).

All Mugger translocations carried out by DWC appeared to be successful, as these animals were released into Mugger habitats, and we did not observe any competition between resident and introduced Muggers.

Loss of human life and injuries

Since 2008, there were eight confirmed human fatalities caused by Saltwater Crocodile attacks; in addition, three people who ‘disappeared’ are believed to have been taken by crocodiles. Twenty-five people were injured during attacks, with injuries ranging from minor to grievous. Most attacks took place in the early morning, late evening or at night. Most of the people who were attacked were males aged over 30 years, and attacks occurred while victims were bathing or carrying out activities in water such as washing clothes, washing kitchenware, collecting aquatic plants, and fishing.

Hindrance for daily activities

The survey indicated that 25% of the people in crocodile habitats enter the water for daily household activities and occupations, and were thus vulnerable to attack. Females were attacked while they were washing clothes. Most attacks in the early morning occurred while people were washing their faces or bathing. Many people are afraid to go to the river, and crocodile attacks have become a common fear in their day-to-day life.

Economic loss

In most of the HCC areas, people are engaged in work-related activities associated with water (e.g., fishing, sand mining, farming, plucking aquatic flowers, prawn farming, and illegal alcohol extraction), and so many of them face difficulties to continue their jobs, and this directly affects their daily income. In addition, Saltwater Crocodiles have entered small farms run by riverine communities, killing livestock (e.g., chickens, cattle, goats) and pets or guard dogs. As Saltwater Crocodiles consume fish (e.g., Oreochromis mossambicus, O. niloticus, Etroplus suratensis, Channa striata, Lates sp.) there is perceived competition for the same food source, and so crocodiles became a common enemy of fishing communities.

Crocodile Vigilance Zones

We identified zones of high HCC incidence involving Saltwater Crocodiles, which we refer to as “Crocodile Vigilance Zones” (CVZ). We identified five CVZs, four of which lie within the wet zone (see Images 2–5) and one which we propose for the dry zone. We stress that there is a risk of increasing HCC within these zones and the possibility of it spreading to surrounding areas in the future unless proper management actions are implemented.

Matara-Malimbada-Akuressa (MMA) Crocodile Vigilance Zone

The MMA CVZ was identified as having the highest rates of killing crocodiles out of fear, road kills, and egg collecting. Matara is a fast developing city and most of the natural vegetation around the Nilwala River floodplains has been replaced with human habitations, agriculture, hotels, restaurants, roads and industrial units. Most of the suitable habitats had consisted of mangroves, but now all the small streams have human encroachment. Saltwater Crocodiles generally prefer small streams connected to the main river close to the sea. We observed some crocodiles digging small underground canals across the bank of the river where most small streams had been ruined. Due to sand mining, there has been saltwater intrusion; at times around 5km or more along the river. This phenomenon may result in Saltwater Crocodiles swimming upriver, perhaps in search of new nesting areas, as most freshwater nesting swamps having been now replaced with saline water and other encroachments. As a result, HCC has recently increased in the upstream Malimbada area, which many crocodiles use for nesting. We observed ideal nesting habitats for Saltwater Crocodile in the Malimbada area, which were not found anywhere downstream along the river, even where there are healthy mangrove habitats. Furthermore the lower plains are regularly flooded and some crocodiles are able to enter the sea and migrate from one river basin to another (e.g., on 19 April 2012, a crocodile ~4.5m long was observed on the Matara seashore, and on 6 January 2012 a crocodile ~3m long was seen in the sea at Matara).

In the Nilwala River, where HCC has increased, we observed many people making small canals towards their home gardens to provide water for their cultivations; we observed that garbage often blocked these canals, which contained a well grown aquatic flora, including Eichhornia crassipes (Pontederiaceae) [see Fig. 5, plate 3 in Karunarathna et al. (2010) for similar invasive aquatic plants, in the waterways of Bellanwila-Attidiya wetland]. This environment makes an ideal habitat and nesting ground for Saltwater Crocodiles. Meat stalls and slaughterhouses pollute the river (e.g., Malimbada area), as do mini chicken-farms beside the river, providing a potential food sources for crocodiles. Many man-eating crocodiles have been killed (using poisoned chicken bait) by villagers around the Nilwala River, and many unplanned translocations were also conducted from this area.

Beruwala-Bentota-Ambalangoda (BBA) Crocodile Vigilance Zone

Bentota is a fast developing tourism zone and the natural vegetation around the Bentota River floodplain is being replaced with housing, hotels, restaurants, roads and other tourism activities. Most of the suitable mangrove habitats and small streams have been replaced with hotels. We observed sea water flowing towards the land around 3km along the river, and many ideal habitats for Saltwater Crocodiles in the Beruwala area have been destroyed. Filling of wetlands, human encroachments, the Beruwala distillery and its water pollution, and tourism were identified as growing threats for Saltwater Crocodiles and their habitats.

Moratuwa-Dehiwala-Wellawatta (MDW) Crocodile Vigilance Zone

The water canals in MDW CVZ are interconnected through the city of Colombo to Kalutara and Beruwela in the south, also Kotte marshes, Diyawanna oya, Kirillapone, Wellawatte, Dehiwela and Nedimale canals to Bellanwila-Attidiya Sanctuary, and then to Bolgoda Lake and then to Kalu River. Furthermore the Mada Ela, starting from Bolgoda Lake, goes as far as Erewwala-Pannipitiya, and is the reason that crocodiles are recorded from the Pannipitiya area. This zone should have been the area of highest HCC, but it was not, due to the high frequency of crocodile hunting (over 120 crocodiles were estimated to have been hunted in 2008–2012) for meat, with most of the meat being sold to tourist hotels around Colombo and Moratuwa. Bolgoda Lake had provided good habitat for Saltwater Crocodiles, but now it is being invaded by human settlements and many areas of the wetland have been filled. The riverine vegetation is destroyed and no suitable habitats remain for crocodile nesting. That is the reason why crocodiles are found in Colombo (on 20 February 2012 a crocodile ~3m long was observed in Colombo Dockyard Sea) and Dehiwala (a ~2m long crocodile was seen in Dehiwala-Wellawatta canal, and a 2m crocodile was seen on 7 February 2012 in Rattanapitiya Canal and Moratuwa, which is interconnected with Bellanwila-Attidiya Sanctuary and Bolgoda Lake by canals).

Ragama-Hendala-Wattala (RHW) Crocodile Vigilance Zone

This narrow canal system fulfills the requirements for Saltwater Crocodile habitat similar to the small streams made by people in MMA CVZ. Most areas of Hamilton Canal are well covered with many aquatic floating plants such as E. crassipes. RHW CVZ has a very high number of meat stalls and slaughterhouses and mini chicken-farms. Also humans have encroached to the margin of the canal and in some areas invaded the canal as well. Muthurajawela and other marshes in Colombo are the main water drainage system, especially during the southwest monsoon.

Kalmune-Batticaloa-Eravur-Kalkuda (KBEK) Crocodile Vigilance Zone

We propose KBEK CVZ, which lies within the dry zone, as an emerging conflict area, and there is a need for immediate surveys to identify the core issues before the conflict becomes worse. The crocodile population data and movement patterns are not well identified for this area, except for a few preliminary surveys that are largely unpublished and local news reports. We strongly suggest protecting the present mangrove and other aquatic vegetation and enriching the habitat.

DISCUSSION

Even though Saltwater Crocodiles are afforded legal protection in Sri Lanka, illegal harvesting of eggs and hunting (direct and incidental) of crocodiles still occur. The current population estimate of 2000 non-hatchlings is considered conservative, and available data suggest that a high proportion of the population comprises immature juveniles, indicative of a recovering population. Despite illegal take of eggs and crocodiles, the population has increased significantly (at mean rate of increase of 5% p.a.) since 1978, when the population was estimated to be 375 non-hatchlings (Whitaker & Whitaker 1979). Our results confirm that crocodilian populations have the ability to recover rapidly if harvest rates are reduced and/or they are afforded protection, and habitats (including nesting habitats) remain intact. The study also confirmed that habitats are under threat largely due to an increasing human population, and the impact of illegal harvesting in the future needs to be addressed.

Both Muggers and Saltwater Crocodiles attack humans (e.g., Caldicott et al. 2005), and are responsible for numerous fatalities each year (Somaweera & de Silva 2013). Crocodile attacks are common in Sri Lanka, in part because there are high numbers of large crocodiles in the population (191 crocodiles sighted were >3m long, and were most likely males; Webb & Manolis 1989), but mainly due to the reliance of increasing numbers of people on water resources that contain crocodiles. HCC is sometimes attributed to overfishing of one of the crocodile’s main food sources, leading crocodiles to hunt other prey, including humans (Uragoda 1994; Rao 1996; Anderson & Pariela 2005). This competition can take the form of theft of live fish from fishing nets and associated damage to fishing gear, and diminishing the daily catch of fishing communities (de Silva 2013).

Notwithstanding the bad image that crocodiles receive as a result of HCC (Santiapillai et al. 2004), our study confirmed previous reports that crocodiles are opportunistically killed or directly hunted for their meat (Senanayake 1995). Whitaker & Whitaker (1977) mentioned that crocodile meat resembles shark meat in terms of taste and texture, and is eaten by people for its purported curative properties (de Silva 2008, 2013).

Attempts by government to mitigate HCC through the translocation of crocodiles do not appear to have taken into account the biology of the species, nor has the effectiveness of this strategy been assessed until now. Muggers are mainly concentrated in national parks and man-made reservoirs in the dry zone (de Silva & Lenin 2010; de Silva 2013), and according to Santiapillai & de Silva (2001) they are sympatric with Saltwater Crocodiles at 25 localities, most of which are uncertain. Previous translocations by DWC assumed that the two species are sympatric, but it appears that these translocations have modified the natural distributions of both species in Sri Lanka, and resulted in mortality of translocated Saltwater Crocodiles due to social interactions with Muggers.

Conservation is an important national and international issue, and it is incumbent upon educators, conservation managers, legal advisors, funding agencies, officials and policy makers to work along with research scientists to ensure that inaccurate information does not endanger efforts to safeguard Sri Lanka’s remaining endangered biodiversity treasures (Bahir & Gabadage 2009), therefore management should be based on the best available information.

Management implications of human-crocodile conflict

Habitat enrichment and restoration

Notwithstanding the issues associated with HCC, the ability of Sri Lanka to maintain healthy wild populations of Saltwater Crocodiles will ultimately depend on the availability of suitable habitats. Habitat loss and destruction, including human encroachment, are the key factors affecting natural Saltwater Crocodile habitats in Sri Lanka. Habitat restoration, including the reintroduction of mangroves on government-owned lands, removal of unpermitted human encroachments from buffer zones of river and swamp areas and resettling of people outside of buffer zones, immediate action to reduce saltwater intrusion into freshwater bodies, restricting the issuing of new permits for sand mining near river mouths (at least 10km from the river mouth), prohibition on the dumping of garbage and farm refuse, and cleaning up garbage and invasive aquatic plants in man-made streams leading into rivers, are actions that can be considered within a strategy to improve and maintain habitat quality in the short- and long-term. As most CVZs are rapidly developing with emergent plans for widening roads and new highways (RDA 2007), the design of new roads should also be considered.

Diverse tourist activities like speed-boats, tourist boat tours and fishing have led to the disappearance of crocodiles (Gramentz 2008) in BBA CVZ. According to Gramentz (2008), at one location along the Bentota River, 39 boats were involved with sand extraction within a 75-minute period. There were no crocodiles recorded in the sea in front of Bentota River (Gramentz 2008), and many crocodiles have migrated to adjacent healthier habitats, which may explain their occurrence on the seashore of BBA CVZ, and recently in Madu Ganga (De Silva & de Silva 2008). We recommend that speed boats not be permitted to enter at least some parts of Dedduwa Lake (e.g., eastern side of Elpitiya Road Bridge) and the upper river. Removal of human encroachments from the buffer zone of the Dedduwa Lake area, and limiting or restricting of sand mining at least as far as the Udugama area, are important. The banning of fishing nets being stretched right across the river and halting of further permissions for new houses or extensions to those already on the bank, with the implementation of enforcement measures, are also recommended (see also Gramentz 2008).

We suggest implementing a proper recycling or disposal plan for the Karadiyana garbage dump in MDW CVZ. In addition, cleaning the canals in Dehiwala, Wellawatta, Colombo area, the reintroduction of mangroves to Bolgoda Lake, and the removal of unpermitted human encroachments, meat stalls and slaughterhouses from Dehiwala-Wellawatta canal buffer zone is very important and urgent. The current wetland fills and unplanned developments will lead to future flooding in Colombo, a similar scenario to that in Jakarta, Indonesia (Caljouw et al. 2005). Devapriya (2004) observed 20 Saltwater Crocodiles along a 2.8-km stretch of the Dandugam Oya and 2–9 individuals in 1.7km of adjacent marsh, showing that they move from Negombo Lagoon to adjacent river basins.

The Dutch Canal, commenced in 1802, links the Kelani River with the main seaport of Negombo Lagoon, and was intended to drain the Muthurajawela Marsh. However the effect was the opposite and the high tides brought in a larger amount of saline water. This created ideal habitats for Saltwater Crocodiles and they bred well in these canals. This was the reason for the increase in HCC in RHW CVZ associated with Hamilton Canal. Also this canal network gives access to Saltwater Crocodiles to the main channel of the Kelani River, a major reason why some have been recorded from Awissawella, over 50 km away inland from RHW CVZ. Removal of unpermitted human encroachments, meat stalls and slaughterhouses from Hamilton Canal and maintaining a buffer zone, stopping the dumping garbage and farm refuse into the canal, and cleaning up garbage and invasive aquatic plants in the canal are considered important and urgent actions.

Awareness

Crocodiles are mostly killed by people out of fear of attacks (Senanayake 1995), and has contributed to the existing bad image that crocodiles have (Santiapillai et al. 2004). Nowadays, the public’s attitude towards crocodiles is ‘negative’, and crocodiles are simply regarded as man-eaters, monsters and killers. The importance of public awareness was pointed out over 35 years ago by Whitaker & Whitaker (1979), when the frequency of HCC was low. Now HCC has increased, and there is a need at a national level for increased public education and awareness about crocodiles.

Effective conservation of Saltwater Crocodiles will involve a diverse range of stakeholders, including Government agencies, non-government organisations, business and tourism sectors, the media, the public (rural and urban), etc., each of which may need to be involved with or be the target of a dedicated public education and awareness program. Crocodiles potentially “involve” a suite of government jurisdictions other than DWC, and so it is important that these other agencies (e.g., transport, tourism, housing, agriculture, water, fishing, police, military) are aware of crocodile management initiatives and environmental legislation as it pertains to crocodiles and other wildlife. Ideally everyone should be rowing in the same direction!

Saltwater Crocodiles are large predators, and humans are well within the size of prey that can be taken. Thus, public education about crocodiles should inform people about the real dangers and realities of ‘living with crocodiles’, but also convey the reasons why crocodiles need to be conserved. Getting that message across to the diverse range of stakeholders in Sri Lanka will no doubt involve a suite of different strategies, ranging from brochures, pamphlets, signage, media coverage, school curriculum (Beehler 2011), T-shirts, calendars, posters, public presentations, tourist guides, museum exhibits, etc. To the extent possible, the media should present a balanced view on crocodiles, as it is an important vehicle to assist public education.

Crocodile Exclusion Enclosures (CEE) have been used effectively in Sri Lanka, and have no doubt contributed to reductions in HCC. However, the significant cost involved with the construction and ongoing maintenance of CEEs has constrained the Sri Lankan Government’s plans to build more of them (CSG 2015a). A mechanism through which local communities can facilitate and contribute to the construction of CEEs merits consideration - it would not only speed up the implementation of CEEs in areas of HCC, but give communities a sense of ownership (CSG 2015a). Other initiatives, such as the provision of water pipelines to rural communities would improve the quality of drinking water, and reduce the reliance on people to carry out some activities near/in crocodile habitats.

Translocation

The effectiveness of translocation as a suitable management option for the mitigation of HCC with Saltwater Crocodiles within a Sri Lankan context is unclear. Saltwater Crocodiles have a strong homing instinct, and translocation may result in return to the original capture site (Webb & Manolis 1989; Walsh & Whitehead 1993; Read et al. 2007). In northern Australia, translocated Saltwater Crocodiles appear to become more mobile, and two Saltwater Crocodiles were subsequently involved in attacks on humans. Translocation of Saltwater Crocodiles into the wild may thus not be an effective strategy for managing HCC, and may indeed exacerbate it.

We suggest that only ‘problem’ crocodiles which have been involved in attacks or which pose a real threat to humans and livestock be captured and translocated, and that this be to captive facilities (see later). Government agencies may need to develop guidelines on appropriate capture and handling techniques. At an international level, some countries have implemented Codes of Practice that have been applied to both wild and captive crocodilians (e.g., NRMCC 2009; CFAZ 2012), and which also take into account animal welfare considerations (see Image 11).

National surveys and research projects

We suggest that a population monitoring program be developed to quantify population trends in different parts of the country over time, and to identify further CVZs and threats to crocodiles and people. The frequency of crocodile attacks, size structure of the population, extent of nesting, etc., could provide additional indices of the population that can help guide management. DWC, in collaboration with local researchers, is planning a national survey of crocodiles, and it is greatly appreciated that DWC will initiate such ground level research towards proper science-based management.

Ex situ or semi in situ conservation (Crocodile National Park)

A captive or semi-natural reserve could assist conservation efforts for crocodiles in Sri Lanka, as was suggested in the 1970s by Whitaker & Whitaker (1979). Such a reserve or facility would not only provide a site for release of problem crocodiles captured to reduce HCC, but could also serve as a centre of public education, training (local and international participants), captive breeding, research and recreation (tourism). Kirala-Kale (Matara District), an 1800ha area, is considered to be the most potential location for a crocodile park or crocodile reserve. Although locations near Colombo may have certain advantages, there are also disadvantages. Wetlands near Colombo are interconnected with many canals up to Chilaw Lagoon (north) and Kalu River (south), in addition to being connected with many other lakes and rivers. These wetlands are also situated in the densely populated capital, so there is a risk of animals escaping and moving to golf course pools, Diyawanna Oya, Bera Lake, Bolgoda Lake, Bellanwila-Aththidiya Marsh, Colombo and Hamilton Canal, and to the sea or dock yard. And there is already a stable population of crocodiles in Muthurajawela Sanctuary and Bellanwila-Attidiya. Furthermore, crocodiles are still being killed in the Muthurajwela area for meat and skins (Devapriya 2004), and we observed illegal crocodile egg collectors in those areas during the course of this study.

Future management

Under current regulations in Sri Lanka there is little opportunity for the development of programs based on the sustainable use of crocodiles. Yet this concept has assisted many countries to recover their crocodilian populations (CSG 2015b). A crocodile park (see above) could provide the first step towards a program based on the sustainable use of Saltwater Crocodiles, through the use of excess stock produced from breeding within the facility. Importantly, it could also provide opportunities for economic development for low-income communities in the area.

It is often local communities that must bear the physical and economic costs of living with crocodiles (McGregor 2005), and the economic value (consumptive and/or non-consumptive) of crocodilians, particularly Saltwater Crocodiles, is the typically strongest incentive for the public to conserve and tolerate large populations of them (e.g., Webb 2000; Hutton & Webb 2002). There is considerable knowledge on the management of Saltwater Crocodiles in other countries, which may assist Sri Lanka with its future efforts. However, every country is different, and crocodile management in Sri Lanka will need to take into account the economic, social and cultural context of the country.

As the lead agency for crocodiles in Sri Lanka, improving DWC’s capacity to deal with HCC and crocodile management in general, and increasing scientific capacity (Pethiyagoda et al. 2007; Bahir & Gabadage 2009; Amarasinghe et al. 2014) will no doubt assist the country’s efforts to ensure the long-term conservation of Saltwater Crocodiles and their habitats.

references

Allen, G.R. (1974). The Marine Crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, from Ponape, Eastern Caroline Islands, with notes on food habits of crocodiles from the Palau Archipelago. Copeia 1974: 553.

Amarasinghe, A.A.T., D.M.S.S. Karunarathna, J. Hallermann, J. Fujinuma, H. Grillitsch & P.D. Campbell (A new species of the genus Calotes (Squamata: Agamidae) from high elevations of the Knuckles Massif of Sri Lanka. Zootaxa 3785: 59–78.

Anand, V.V., S. Senadheera & T. Rupatunge (2013). A view on Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) captured from anthropogenic habitats in western province, Sri Lanka, pp. 258–260. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Anderson, J. & F. Pariela (eds.) (2005). Strategies to Mitigate Human-Wildlife Conflict in Mozambique. Report for the National Directorate of Forests and Wildlife, Mozambique. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

Bahir, M.M. & D.E. Gabadage (2009). Taxonomic and scientific inaccuracies in a consultancy report on biodiversity: a cautionary note. Journal of Threatened Taxa 1(6): 317–322; http://dx.doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o2123.317-22

Estimating the abundance of Saltwater Crocodiles, Crocodylus porosus Schneider in tidal wetlands of the N.T.: A mark-recapture experiment to correct spotlight counts to absolute numbers and the calibration of helicopter and spotlight counts. Australian Wildlife Research 13: 309–320.

Natural History Today and Tomorrow. Taprobanica 3: 50–51.

Home range and movements of radio-tracked Estuarine Crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) within a non-tidal waterhole. Wildlife Research 35: 140–149.

Caldicott, D.G.E., D. Croser, C. Manolis, G. Webb & A. Britton (2005). Crocodile attacks in Australia. An analysis of its incidence, and review of the pathology and management of crocodilian attacks in general. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 16(3): 143–159.

Caljouw, M., P.J.M. Nas & Pratiwo (2005). Flooding in Jakarta: Towards a blue city with improved water management. Bijdragen tot de Taal- Land- en Volkenkunde 161(4): 454–484.

Campbell, H.A., R.G. Dwyer, T.R. Irwin & C.E. Franklin (2013). Home range utilisation and long-range movement of estuarine crocodiles during the breeding and nesting season. PLoS ONE 8(5): e62127.

Campbell, H.A., R.G. Dwyer, H. Wilson, T.R. Irwin & C.E. Franklin (2014). Predicting the probability of large carnivore occurance: a strategy to promote crocodile and human coexistance. Animal Conservation (early view); http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acv.12186

Cincotta, R.P., J. Wisnewski & R. Engelman (2000). Human populations in the biodiversity hotspots. Nature 404: 990–992.

CFAZ (Crocodile Farmers Association of Zimbabwe) (2012). Codes of Practice. CFAZ, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Cooper, P.H. & R.W.G. Jenkins (1993). Natural history of the Crocodylia. pp. 337–349. In: Glasby, C.J., G.J.B. Ross & P.L. Beesley (eds.). Fauna of Australia, Amphibia and Reptilia. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, Australia.

CSG (Crocodile Specialist Group) (2015a). Human-Crocodile Conflict; Crocodile Exclusion Enclosures (CEEs). http://www.iucncsg.org/pages/Human%252dCrocodile-Conflict.html.

CSG (Crocodile Specialist Group) (2015b). Sustainable utilization. http://www.iucncsg.org/pages/Sustainable-Utilization.html.

Deraniyagala, P.E.P. (1939). The Tetrapod Reptiles of Ceylon, Testudinates and Crocodilians. National Museums of Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 412.

de Silva, A. (2008). Preliminary survey of Saltwater Crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) in the Nilwala River, Sri Lanka. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 27: 10–13.

de Silva, A. (2013). The Crocodiles of Sri Lanka (Including Archaeology, History, Folklore, Traditional Medicine, Human-Crocodile Conflict and a Bibliography of the Literature on Crocodiles of Sri Lanka). AMP Print Shop, Gampola, Sri Lanka.

de Silva, A. & J. Lenin (2010). Mugger Crocodile Crocodylus palustris. pp. 94–98. In: Manolis, S.C. & C. Stevenson (eds.). Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Crocodile Specialist Group, Darwin, Australia.

de Silva, M. & A. de Silva (2008). Record of Crocodylus porosus nest from Sri Lanka. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 27: 13–14.

Devapriya, W.S. (2004). A survey of the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) in the Muthurajawela urban marsh. Lyriocephalus 5: 25–26.

Erickson, G.M., P.M. Gignac, S.J. Steppan, A.K. Lappin, K.A. Vliet, Breuggen, J.D., Inouye, B.D., Kledzik, D. and G.J.W. Webb (2012). Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodilians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation. PlosOne 7: e31781.

Gramentz, D. (2008). The distribution, abundance and threat of the Saltwater Crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, in the Bentota Ganga, Sri Lanka, 16pp.

Hanson, J.O., S.W. Salisbury, H.A. Campbell, R.G. Dwyer, T.D. Jardine & C.E. Franklin (2014). Feeding across the food web: The interaction between diet, movement and body size in estuarine crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus). Austral Ecology (early view); http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/aec.12212

Hutton, J. & G. Webb (2002). Legal trade snaps back: using the experience of crocodilians to draw lessons on regulation of the wildlife trade, pp. 1–10. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 16th Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Jayawardene, J. (2004). Conservation and management of the two species of Sri Lankan Crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus and Crocodylus palustris). pp. 155–165. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 17th Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Karunarathna, D.M.S.S., A.A.T. Amarasinghe, D.E. Gabadage, M.M. Bahir & L.E. Harding (2010). Current status of faunal diversity in Bellanwila-Attidiya Sanctuary, Colombo District, Sri Lanka. Taprobanica 2: 48–63.

Movements and home ranges of radio-tracked Crocodylus porosus in the Cambridge Gulf region of Western Australia. Wildlife Research 31: 495–508.

Lamarque, F., J. Anderson, R. Fergusson, M. Lagrange, Y. Osei-Owusu & L. Bakker (2009). Human-wildlife conflict in Africa: Causes, consequences and management strategies. Food and Agriculture organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, 98pp.

Changes in the distribution and abundance of Saltwater Crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) in the upstream, freshwater reaches of rivers in the Northern Territory, Australia. Wildlife Research 33: 529–538.

Manolis, C. (2005). Long-distance movement by a Saltwater Crocodile. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 24: 18.

McGregor, J. (2005). Crocodile crimes: people versus wildlife and the politics of postcolonial conservation on Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe. Geoforum 36: 353–369.

MOE (2012). The National Red List 2012 of Sri Lanka: Conservation Status of the Fauna and Flora. Ministry of Environment, Colombo, Sri Lanka: 476.

NRMMC (Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council) (2009). Code of Practice for the Humane Treatment of Wild and Farmed Australian Crocodiles. NRMMC, Canberra, Australia.

Pethiyagoda, R., N. Gunatilleke, M. de Silva, S. Kotagama, S. Gunatilleke, P. de Silva, M. Meegaskumbura, P. Fernando, S. Ratnayeke, J. Jayewardene, D. Raheem, S. Benjamin & A. Ilangakoon (2007). Science and biodiversity: the predicament of Sri Lanka. Current Science 92: 426–427.

Porej, D. (2004). A case study of the Saltwater Crocodile Crocodylus porosus in Muthurajawela Marsh, Sri Lanka - Considerations for conservation. Journal of Bombay Natural History Society 101: 337–343.

Rao, M.V.S. (1996). Nesting behaviour of the Indian crocodiles, Gavialis gangeticus, Crocodylus palustris and Crocodylus porosus, pp. 212–216. In: Ramamurthi, R. & Geetabali (eds.). Readings in Behaviour. Newage International Ltd, New Delhi, India.

RDA (2007). National Road Master Plan of Sri Lanka 2007–2017. Road Development Authority, Government of Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 37pp.

Read, M.A., G.C. Grigg, S.R. Irwin, D. Shanahan & C.E. Franklin (2007). Satellite tracking reveals long distance coastal travel and homing by translocated Estuarine Crocodiles, Crocodylus porosus. PlosOne 2: e949.

Samarasinghe, D.J.S. (2014). The Human-Crocodile Conflict in Nilwala River, Matara (Phase 1). YZA Publications, Dehiwala, Sri Lanka, 86pp.

Santiapillai, C. & M. de Silva (2001). Status, distribution and conservation of crocodiles in Sri Lanka. Biological Conservation 97: 305–318.

Santiapillai, C., S. Wijeyamohan, R. Vandercone & R. Somaweera (2004). Crocodiles of Sri Lanka. Mannar District Rehabilitation and Reconstruction through Community Approach Project (www. manrecap.com).

Senanayake, N. (1995). Human and reptile conflicts: impact on reptiles in Sri Lanka. Lyriocephalus 2: 86.

Somaweera, R. & A. de Silva (2013). Using traditional knowledge to minimize human-crocodile conflict in Sri Lanka, pp. 257. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Taylor, J.A. (1979). The foods and feeding habits of subadult Crocodylus porosus Schneider in northern Australia. Australian Wildlife Research 6: 347–359.

Uragoda, C.G. (1994). Wildlife Conservation Sri Lanka. Wildlife and Nature Protection Society, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 162pp.

Walsh, B. & P.J. Whitehead (1993). Problem crocodiles, Crocodylus porosus, at Nhulunbuy, Northern Territory: an assessment of relocation as a management strategy. Wildlife Research 20: 127–135.

Webb, G.J.W. (2000). Sustainable use of large reptiles - an introduction to issues. pp. 413–430. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 15th Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Webb, G.J.W., M.L. Dillon, G.E. McLean, S.C. Manolis & B. Ottley (1990). Monitoring the recovery of the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) population in the Northern Territory of Australia. pp. 329–380. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 9th Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Webb, G. & C. Manolis (1989). Crocodiles of Australia. Reed Books, Frenchs Forest, Australia,

Webb, G.J.W. & H. Messel (1978). Movement and dispersal patterns of Crocodylus porosus in some rivers of Arnhem Land, northern Australia. Australian Wildlife Research 5: 263–283.

Whitaker, R. (2004). Regional report from CSG Vice Chairman for South Asia. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 23: 8–9.

Whitaker, R. & N. Whitaker (2008). Who’s got the biggest? Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 27: 26–30.

Whitaker, R. & Z. Whitaker (1977). Sri Lanka crocodile survey. Loris 14: 239–241.

Whitaker, R. & Z. Whitaker (1979). Preliminary crocodile survey - Sri Lanka. Journal of Bombay Natural History Society 76: 66–85.

Wittemyer, G., P. Elsen, W.T. Bean, A.C.O. Burton & J.S. Brashares (2008). Accelerated human population growth at protected area edges. Science 321: 123–126.

Woodroffe, R., S. Thirgood & A. Rabinowitz (2005). People and Wildlife: Conflict or Coexistence. Cambridge University Press, UK, 516pp.